I don’t do this often, but when a book comes highly recommended by the Sage of Northampton, bears a foreword written by him, and is signed by both the author and the Foreword Writer, I do not argue with Fate. Bought immediately, and paid for international shipping too. The reviews on Amazon are glorious, and reminds me of pre-Jonathan Strange/Mr Norrell buzz for Susanna Clarke. (And that reminds me that I should probably reread that book too).

From the foreword:

A genre that has been reduced by lazy stylisation to a narrow lexicon of signifiers … wizards, warriors, dwarves and dragons … is a genre with no room for Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, arguably the earliest picaresque questing fantasy; for David Lindsay’s Voyage to Arcturus with its constantly morphing vistas and transmogrifying characters; for Mervyn Peake’s extraordinary Gormenghast books or for Michael Moorcock’s cut-silk Gloriana. It is certainly a genre insufficient to contain the vegetable eternities of Catling’s Vorrh.

Here’s where you can buy a signed copy. (No guarantees though, as the small print says.) Apparently all of the signed copies are sold out, and I got one. The confirmation email came in today morning.

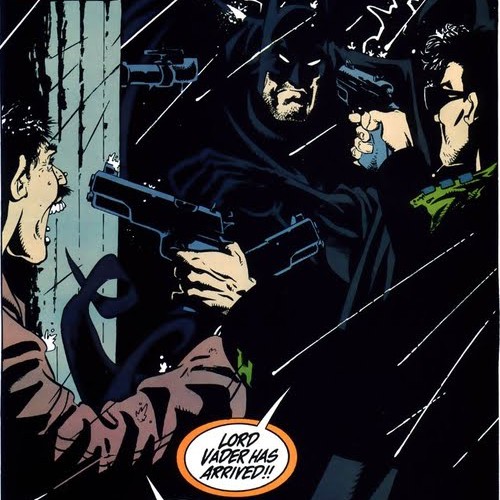

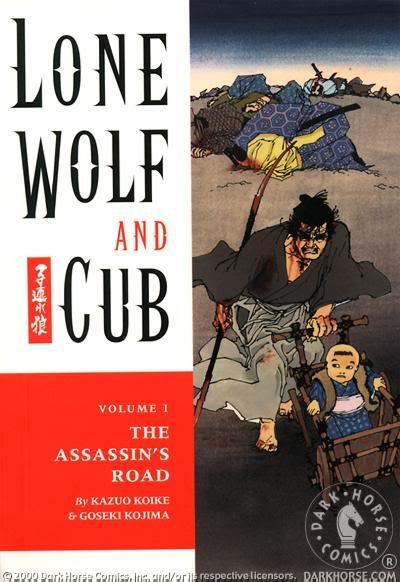

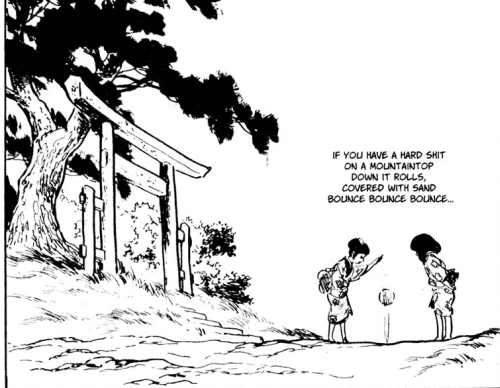

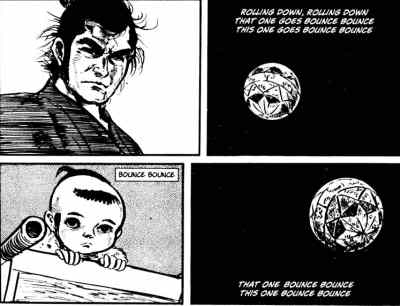

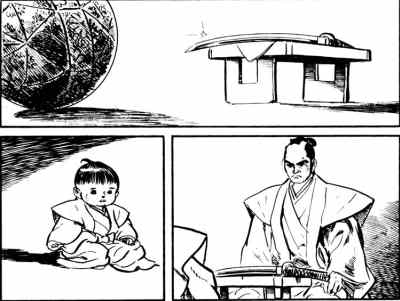

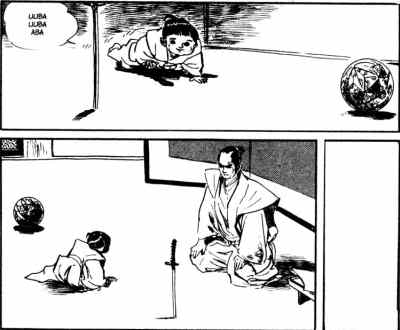

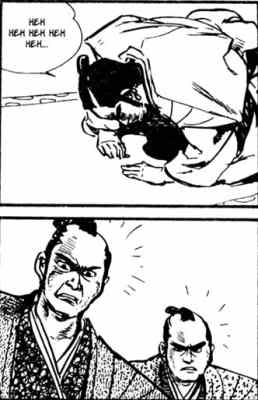

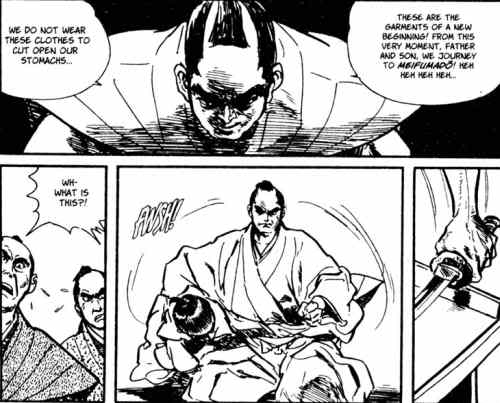

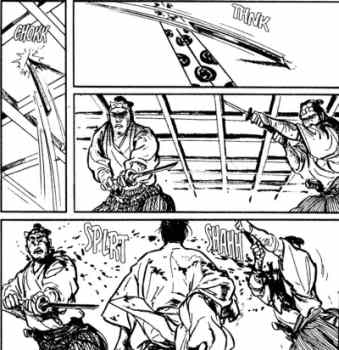

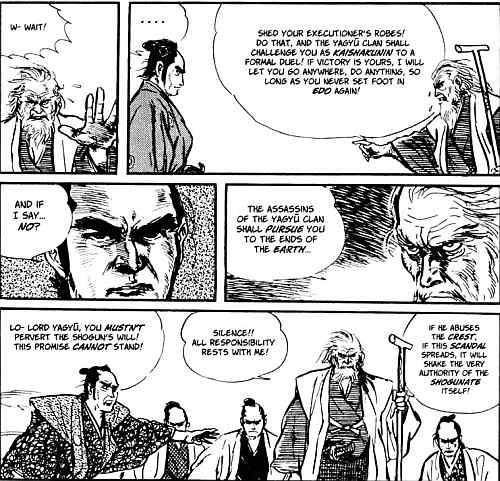

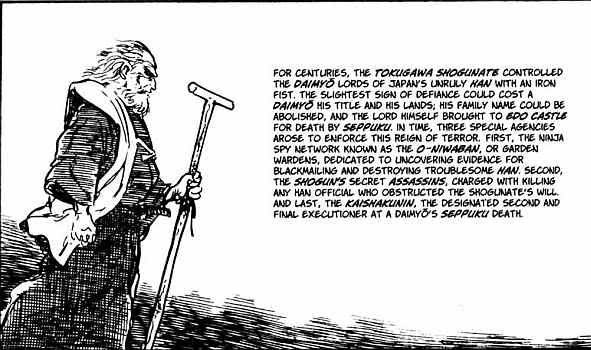

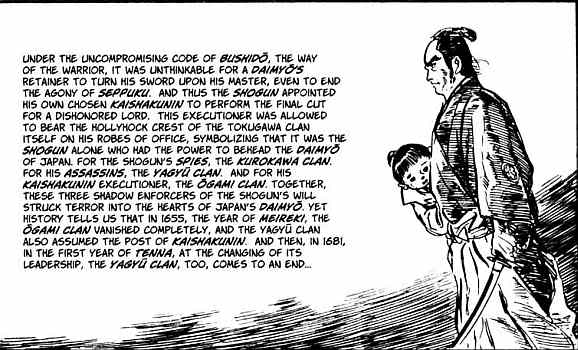

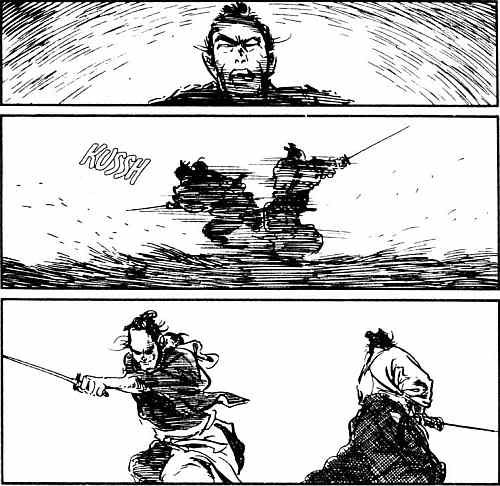

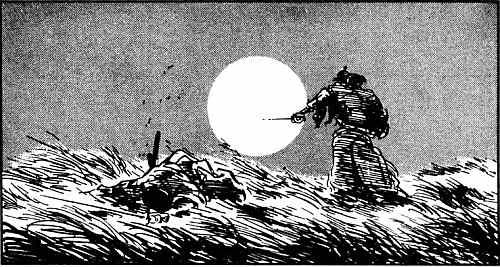

Other than that, I have been rereading some old manga favorites. Among them is Crying Freeman. I bought the complete Dark Horse set a while ago at the low low price of $1 per volume – I have the Viz comics and you will agree that reading them pamphlets gets a little annoying, even though some of the coloring adds to the eightiesness of the series. It’s over-the-top seinen action, with lots of photo-referenced art by Ryoichi Ikegami, and it is just as I remembered it – brimming with the kind of content that sets librarians and conscientious parents aflutter, the kind of salacious visuals that attracts giggling clusters of school-kids in Landmark, where the books stay misfiled in the children’s section. Crying Freeman is the kind of thing Dr. Fredric Wertham warned the world about, people. Do not file it in the children’s section, not unless you want kids to wonder why women have white areas in their groin, whether Chinese assassins really strip to their underwear before jumping up on Russian wrestlers’ shoulders, and if it is possible for a man to cover himself in cement and not burn to a crisp when attacked by a janitor with a flame-thrower. And how a Japanese man can be a master artist, a master assassin, and the Greatest Lover Ever. This book is testament to the fact that manga writer Kazuo Koike is what Stan Lee would be without the Comics Code Authority to keep him in check. And Crying Freeman is what an Amitabh Bachchan character would really be in the 70s, without the castration anxiety of the Indian Censor Board. Mull about the ocean of possibilities for a while.

This reminds me that the high-point of Comicon this year was getting to meet Koike in the flesh. I queued to meet him three times, just because there was a 2-item cap on signatures; I probably would have gone a few more times had there not been other events to attend. Kazuo Koike, man. Never thought I would get to thank him in person. Insert a twenty-one gun salute moment for Dark Horse Comics here.

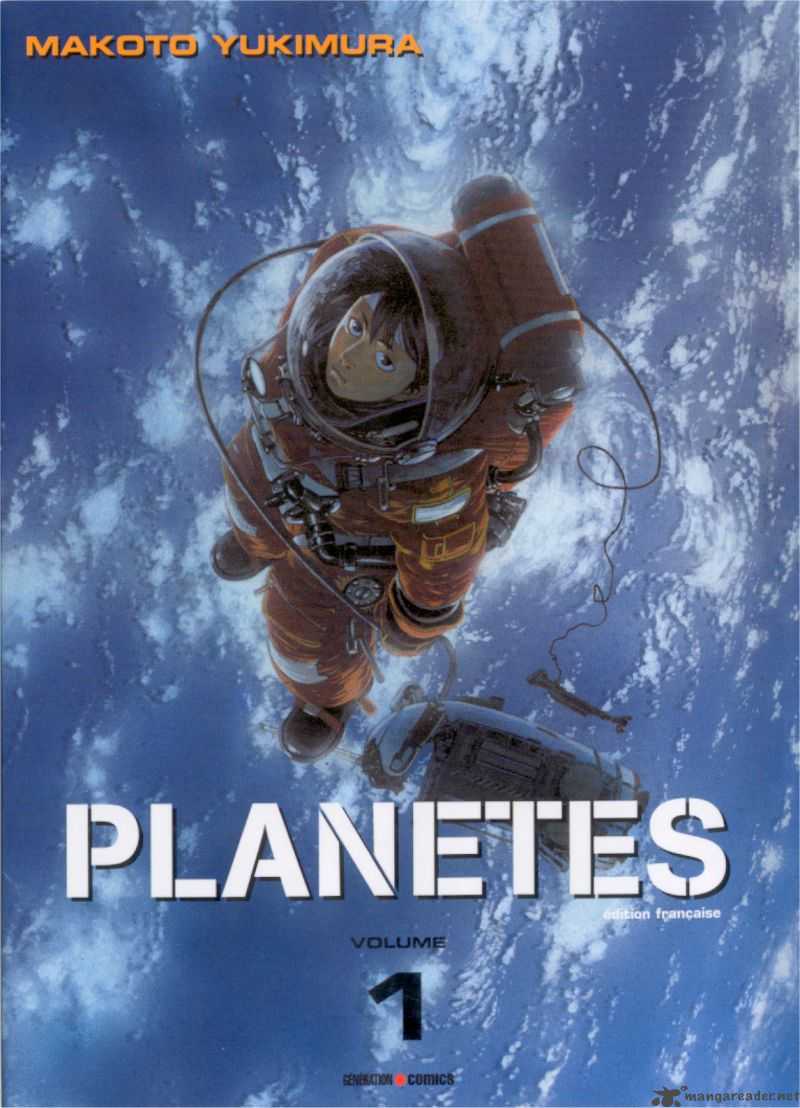

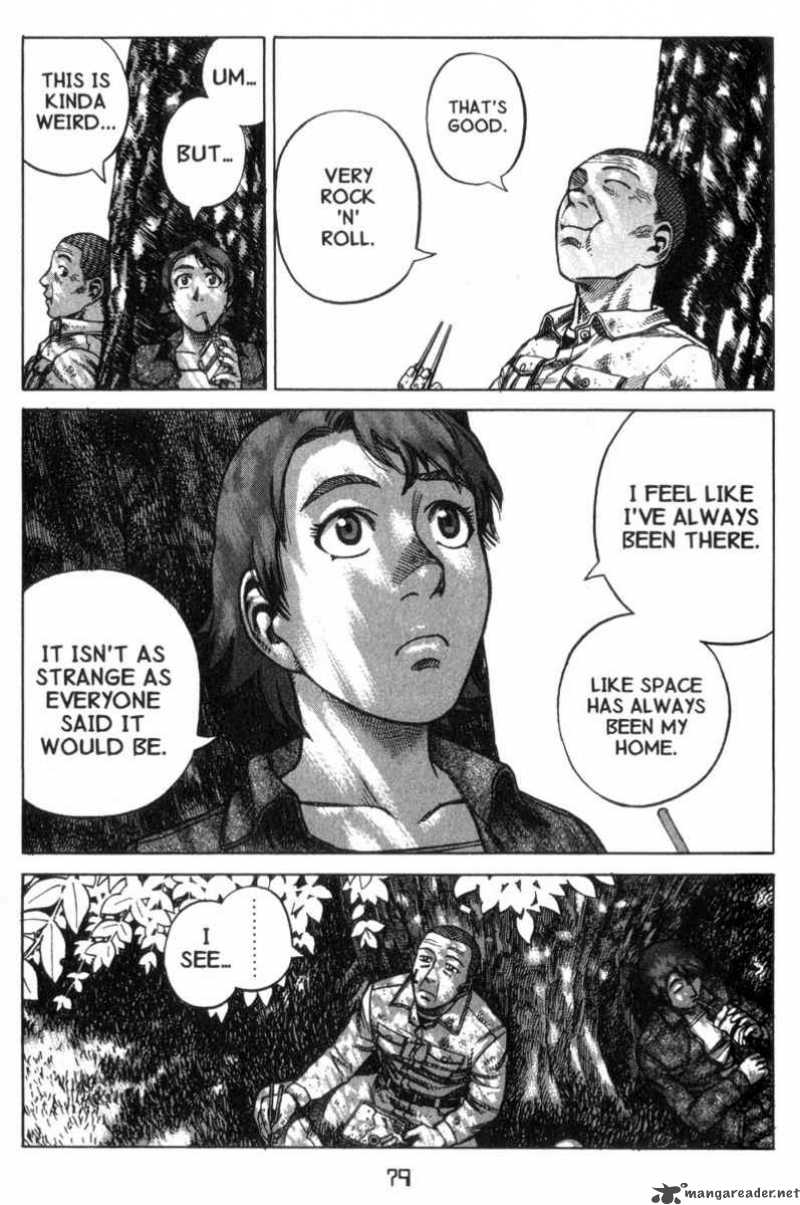

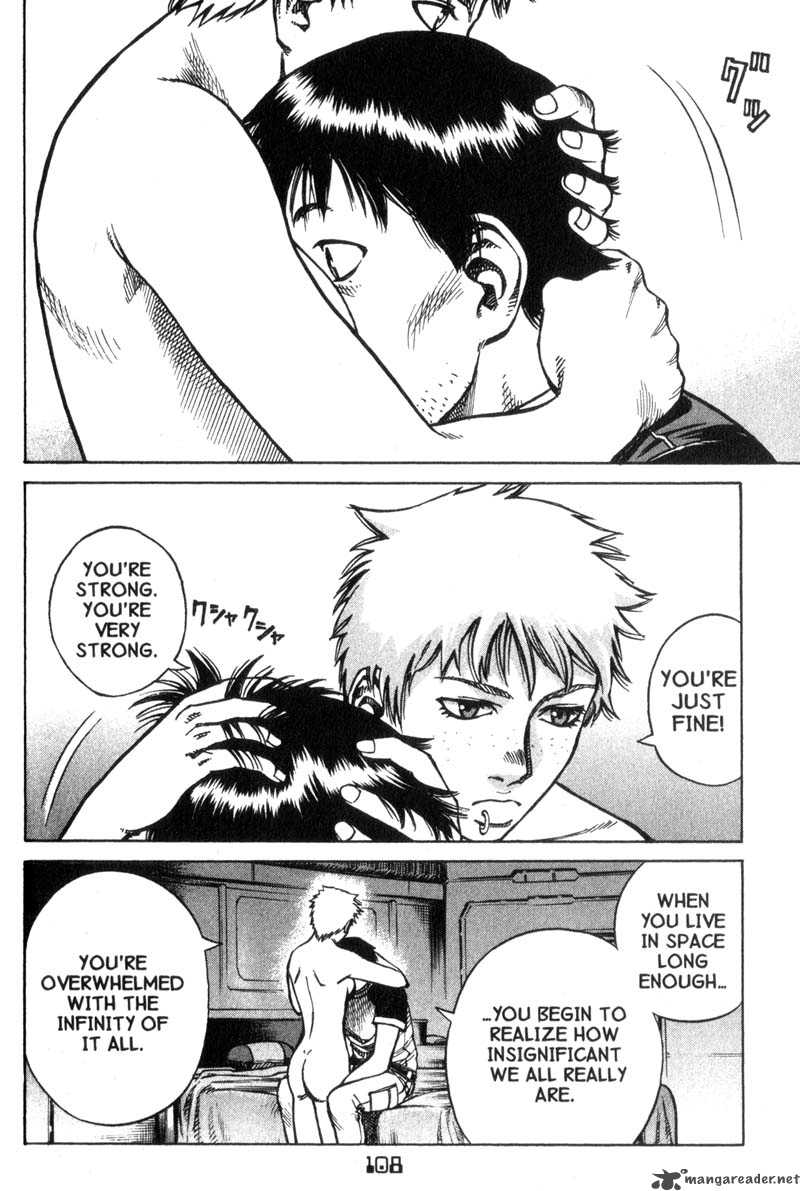

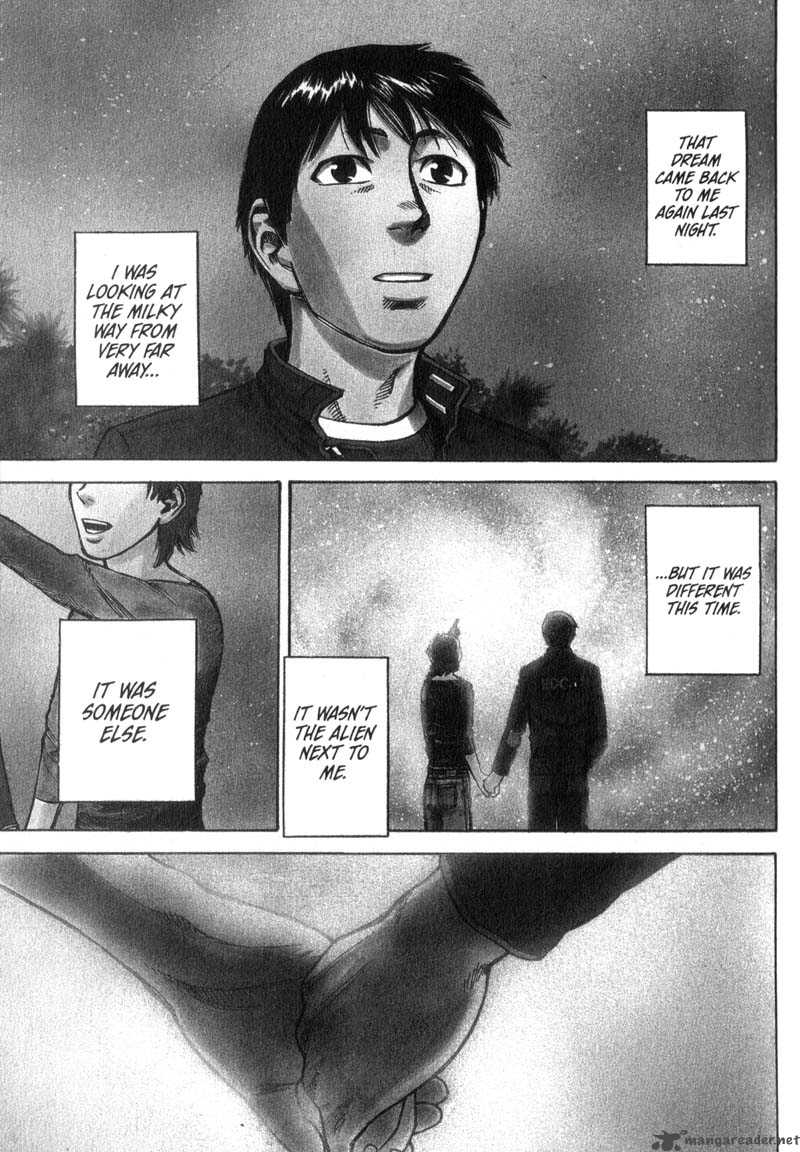

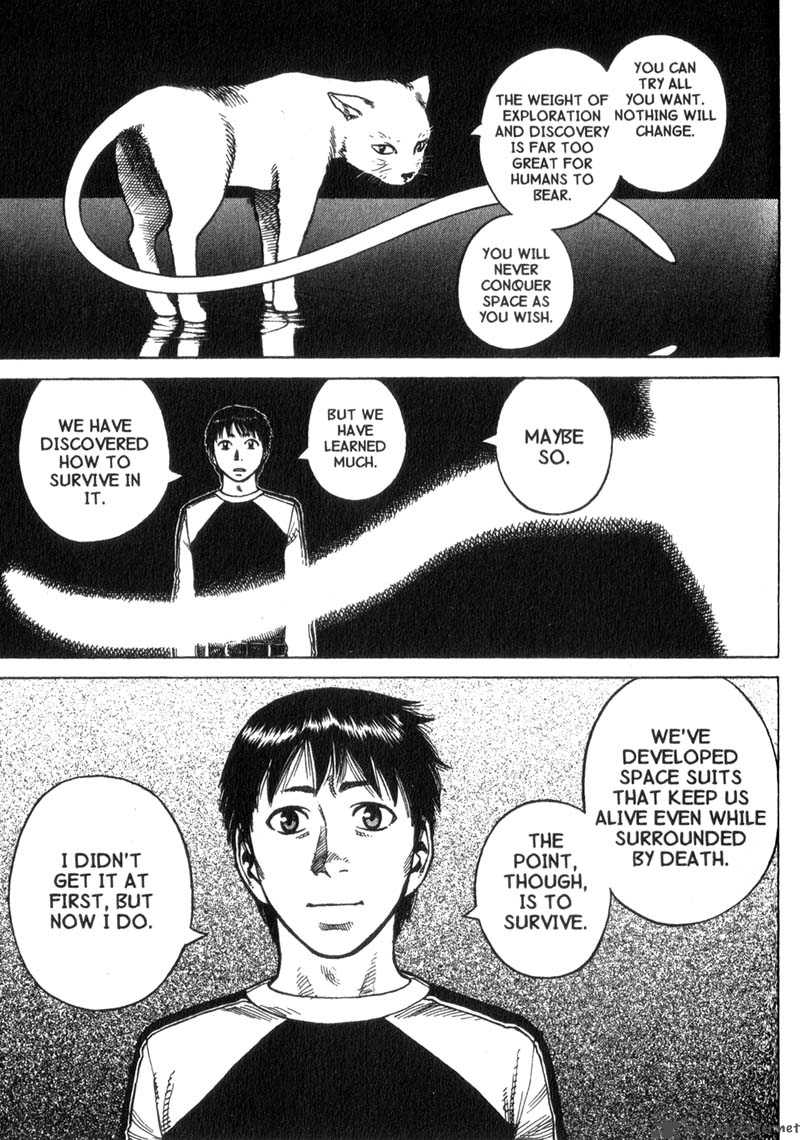

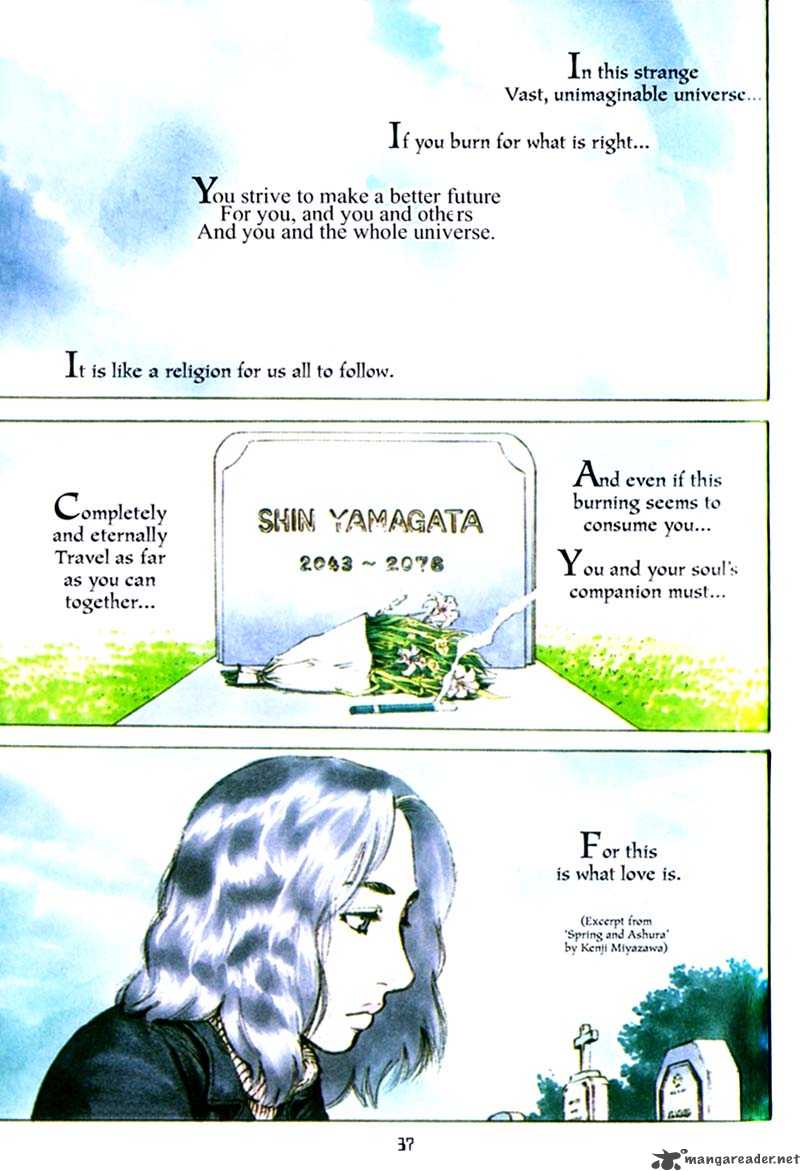

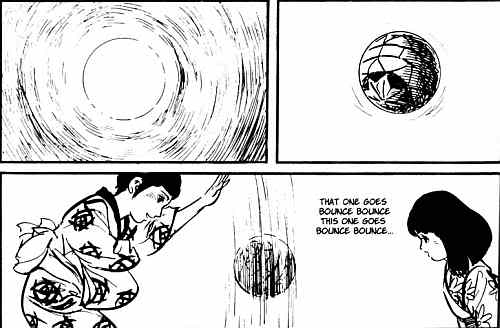

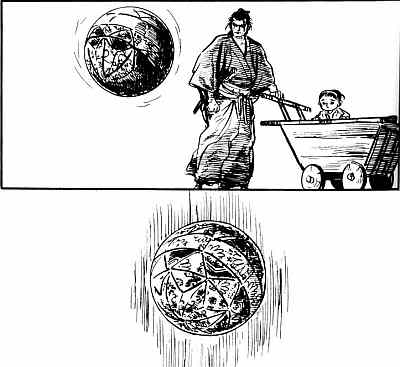

The other series I read – after a gap of nearly seven years – was Planetes by Makoto Yukimura. Long out of print, I picked up the series on a whim from a collector whose bookshelves I emptied back when I was an established Emptier of Bookshelves, a veritable patron saint of Liquidators. (Ironically, swathes of my floppy comics are now making their way to different parts of the world, as I succumb to Omnibus upgrades). Coming back to Planetes, this is the sort of manga that serves as a gateway to anyone not used to the medium. It’s a series of interconnected glimpses into the lives of a motley crew on board an orbiting garbage disposal unit, set in the year 2070 or thereabouts, when mankind has made a little more progress in space travel. Over the course of 5 volumes, we see how the passage of time affects the daily lives of the astronauts, how their lives and those of the ones they love have intertwined, and the effect that a planned Jupiter Exploration has on them. It is the kind of manga that floats around in your brain after you have finished reading it, with a bewildering attention to detail and a penchant for capturing the exact texture of a moment in time. If you have read Ba/Moon’s Daytripper or Thompson’s Blankets, you know what I mean. It’s a shame it’s not available on the market at the moment, I wish someone like Vertical would bring it back in an Omnibus (they totally can, it’s Kodansha). I would probably buy it for everyone I know.

There is an anime based on the series. I know it’s good, from all the buzz I have heard about it, but I have to finish it some time. I stopped at 2 episodes the last time I started. Or you can read the manga online, for free.