Pal Amulya is full of book-related questions, and I can talk about books all the time. This is from a Facebook meme that involves naming 10 books that stayed with you. Shit like this is tough because number-bound lists suck yada yada and well okay, these are some books that I keep going back to. It is also a list that surprised me.

The rules are: No comics. Cool? Cool.

1. Alexandre Dumas – The Count of Monte Cristo

I have talked about this book before. Instead of adding to the yakkery, allow me to point you to a painting. It’s an illustration of the Count done by artist Mead Schaeffer in the 1920s, one magnificent painting that arrests your attention. I was lucky enough to see it in person at the Weismann Museum at Pepperdine University, Malibu last year, and it gave me the fucking chills.

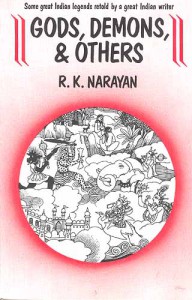

2. RK Narayan – Gods, Demons and Others

This was the cover to the version I bought

I was ten, and this was a book I had finished reading in a week, after buying it at the Guwahati Book Fair. A friend’s father borrowed it, and when he came home to return it, a month later, he was much surprised to know how fast I was done with the book. “Did you really read it?”, he asked. Smiling at my indignant yes, he opened the book and pointed to the first line in the introduction, which had the phrase ‘part and parcel of Indian life’. “What does “part and parcel” mean?”, he asked me. He was a little surprised at my answer, and accepted that I was not fibbing about the speed of my consumption.

But my mind was blown because, for the first time, I realized that the introduction to a book was not necessarily boring and that it should not be skipped over.

I pick this over the Mahabharata, because this was the first prose version of mythological stories I read. And it made me look for more. And also, stunning RK Laxman illustrations that made me wear out my black oil pastels trying to copy them.

(Oh, and I also found a first edition hardcover much later in life)

3. Mark Twain – Adventures of Tom Sawyer/Louisa May Alcott – Little Women

This is how we read books, once upon a deprived childhood. First, we read a chapter excerpt in an English textbook. Then we read an abridged S Chand version. Then we read other abridged versions, and finally graduated to reading the originals, the sequels and the spin-offs. I spent some time in my adolescence thinking about whether I would kiss Becky Thatcher if I was alone in the cave with her. (The answer is yes)

Little Women is perhaps my first feminist novel, even though I did not know it then. Sometimes I feel like the book is a bit too traditional, but then I reread it and – seriously, it’s so fucking progressive.

4. Stephen King – The Shining

When you are traveling with friends on a 2-day train journey, and find yourself sitting in the upper berth unable to breathe, occasionally shivering in the middle of July, and wanting to make sure that there are people around you every now and then, you are a very very bad traveler. Or you are reading this book you picked up on a whim from this pavement seller in Delhi. You don’t know it yet, but it will determine a lot of your tastes in the next decade. You will yearn to find terror in words, and you will realize that it takes a very special writer to produce works that inspire dread, and much later, you will discover his son, who does the same.

(The book is dedicated to “Joe Hill”. Hill’s book NOS4A2 features references to multiple King characters, including a fleeting mention of the True Knot, who appear as the antagonists in Doctor Sleep, the cool-but-somewhat-tepid sequel to Shining)

5. The Mammoth Book of Vampire Stories – Edited by Stephen Jones

These “Mammoth” books proliferated in bookstores around India, and introduced me to a fair amount of new writers that I hadn’t heard of before. This particular volume contained a poem by Neil Gaiman, which made me look up and understand the difference between fixed verse forms, specifically sonnets and sestinae – memory fails me, but this was perhaps the first bit of non-comics Gaiman work I ever read. It had a story by Clive Barker, which pointed me to the wonderful Books of Blood. Brian Lumley’s contribution made me look up his Necroscope books. I had just read the original Dracula, and Stoker’s excised chapter ‘Dracula’s Guest’, included in this volume, made me feel like a happy child (which I was!). And finally, the novella ‘Red Reign’ by Kim Newman, which later became the Anno Dracula series, was my first introduction to a shared fictional universe. Good times!

6. Walter Moers – the Zamonia novels (13.5 Lives of Captain Bluebear/The City of Dreaming Books/Rumo/Labyrinth/Alchemaster’s Apprentice)

I don’t talk about the books I like a lot. The cynical part of me worries that someone I recommend the books to will talk disparagingly of them, and then I will have two options: hate that person forever, or rethink my opinion of the book. Because obviously we cannot all be mature adults respecting each others’ opinions about the books we love, man. So yeah, Walter Moers. If you haven’t read these books, you are missing something. If you don’t like them, don’t tell me, because we are not meant to know each other.

Two regrets: I do not know German well enough to understand how good/bad the translations are, and I did not have an Awesome Uncle to present these books to me when I was younger. Had one existed, the world would have seen a version of me that had Optimus Yarnspinner tattoos and wrote bad Zamonia fan-fiction.

7. George Orwell – 1984

Before this current wave of young adult literature drenched in dystopian futures and all-pervading governmental control, there was Oceania and Winston Smith and Big Brother. It is strange how this book written in the middle of the last century hit on every aspect of modern life that makes us nervous in 2014. I love going back to it, and sometimes I worry that the future is already happening.

8. David Fisher, Anthony Reed – The Proudest Day / Dominique Lapierre, Larry Collins – Freedom at Midnight / Ramachandra Guha – India After Gandhi

These were the books that made recent Indian history interesting to me. History taught in our schools comes to a miraculous end in 1947. The British rule is essentially an Us vs Them saga where They were bad and We were good. These books un-deify the valorous and make them human, and give multiple hues to people who were just names and statistics.

(Also, the section about the first elections in independent India makes me cry, every single time)

9. CD Payne – Youth in Revolt (and its sequels)

This is a California book, and occasionally it becomes a Europe book. Every now and then, I look past the zany antics of Nick Twisp and his crew and contemplate their milieu, the small-town lives of the characters. I read about Nick’s Berkeley catastrophe while passing through Berkeley. Years later, I stayed in a motel in Ukiah while driving north, and it was only later that I realized excitedly that Sheeni grew up in that town. To me, Nick Twisp is the post-modern version of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn combined, and unlike most books whose sequels let you down, these just make you fall in love with the characters even more.

10. Jaron Lanier – Who Owns the Future?

A book that made me question a lot of opinions that I had about the digital economy, particularly piracy and the culture of sharing. These are opinions that I thought were fairly obvious and set in stone, but Lanier’s arguments systematically decimates them and makes me feel like a fool. The book is quotable beyond belief, and has given me one of my favorite words: antinembosian, which means ‘before the cloud’. It is also the reason I would rather write this on my own blog, than on Facebook.