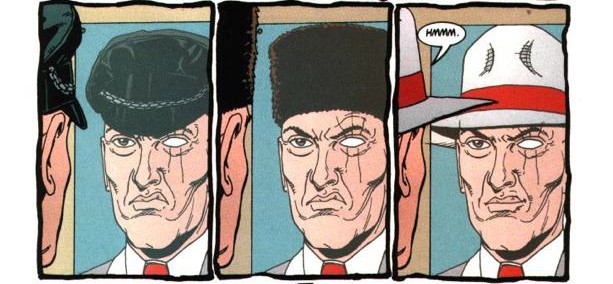

There are a few names that immediately come to mind when you say “horror manga” — Junji Ito, Suehiro Maruo, Hideshi Hino, and Kazuo Umezu (or Umezz, if you prefer). Of these, Umezu is the oldest, born in 1936, and was still making manga as recently as 1995. Beyond his primary career, Umezu is a musician, an actor, screenwriter, and film director. And as the 2009 picture below shows, he’s also a bit of a visual personality.

He’s hugely influential in the manga industry, and the newer crop of horror manga-ka, including Ito have gone on record citing his work as one of their major sources of inspiration. Rumiko Takahashi, known for blockbuster series like Ranma 1/2, Inuyasha, and Maison Ikkoku worked as his assistant early on her career — and I believe you can see shades of Umezu in her short Mermaid Saga.

Sadly, his work has not been widely available in English. Orochi was a single-volume work published by Viz in 2002, and is now unavailable. The two volume Cat-Eyed Boy came out around 2008, and has been unavailable in dead-tree format for about a decade now, though thankfully available on Kindle and Comixology. For the record, this is what I wrote about it in Rolling Stone magazine about this title back in the day:

Kazuo Umezu is known for his gruesome, no-holds-barred comics. One of the of luminaries of the horror manga scene, Umezu knows how to unabashedly press the right buttons on his unsuspecting readers, his stories taking you down uncertain paths in deserted temples, suburban neighborhoods and bucolic villages. The Cat-eyed Boy in the stories is a monstrous-looking creature who plays the omnipresent narrator, at times an onlooker of the ghastly proceedings, and at other times actively involved in the eerie goings-on, leaving you riveted and repulsed at the same time.

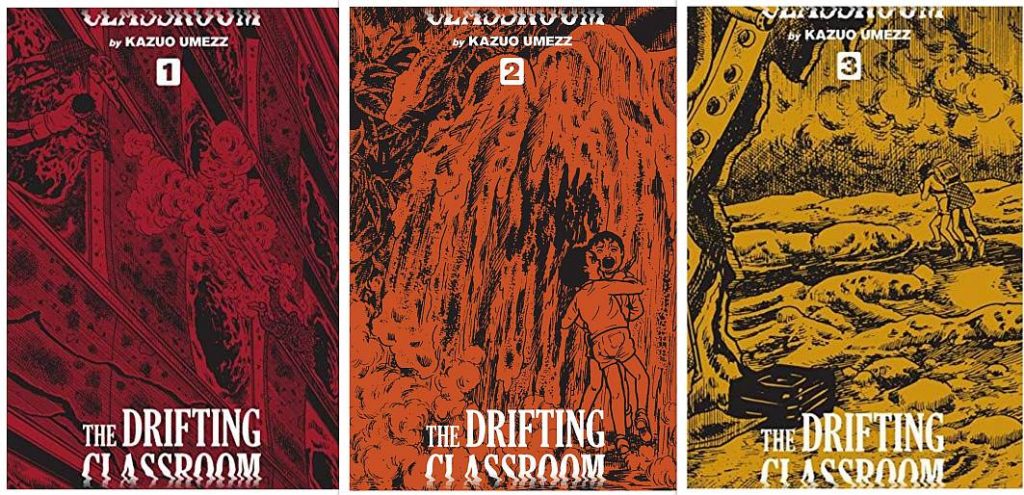

But it is the eleven-volume Drifting Classroom that has been the white whale for completist manga collectors. The series was published in its entirety in 2006, and went out of print. Thankfully, in 2019 Viz chose to republish it in a three-volume hardcover format under its Signature imprint, at a great price point. The books are gorgeously designed volumes, and one of the reasons I jumped on them (other than the chance of these going OOP very soon too), was the visual and tactile experience of the hardcovers. The text you see on the covers are embossed, and the outer surface of the books have a matte texture that makes it feel like a vintage publication. I also dig the glitchy font design, with the word “CLASSROOM”. Its like adjusting an old television set to an alien signal.

This is the official description of the series on Viz’s website:

In the aftermath of a massive earthquake, a Japanese elementary school is transported into a hostile world where the students and teachers are besieged by terrifying creatures and beset by madness.

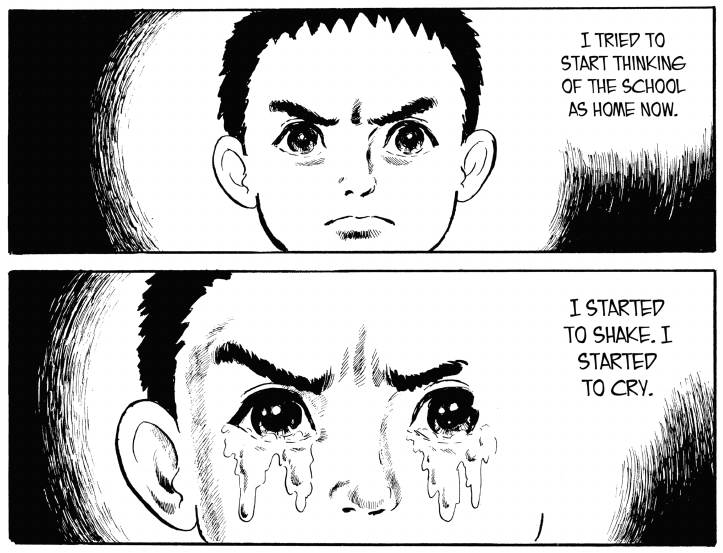

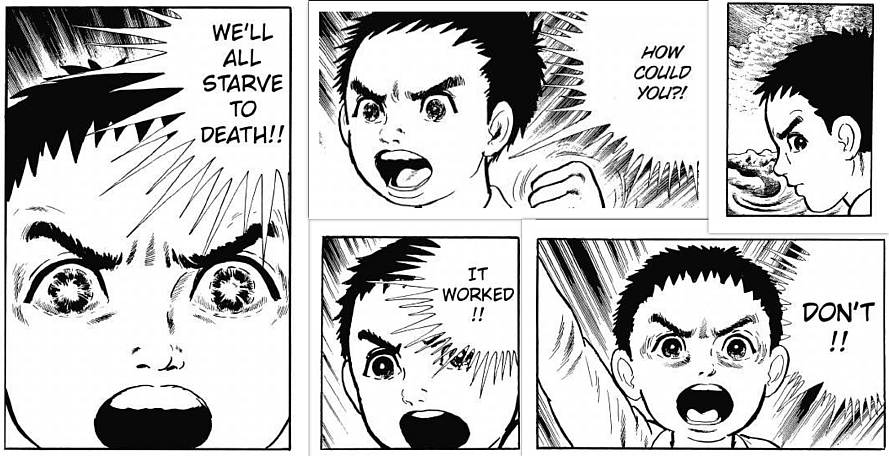

What the summary does not tell you, though, is how the story-line is a series of escalating events that are accompanied by strained nerves, wild revelations, gruesome deaths. There is a mood of panic and fear that propels the story forward, most of it heightened by the anachronistic artwork from Umezu. The series came out in 1973, after all. His style is cartoonish, and does not possess the vocabulary or style of modern manga. The emotional pitch of all characters are set to a default of 8 out of 10, and every setback or stressful situation twists that dial to 200. So, as a reader, that’s the first threshold you have to cross to take the book seriously.

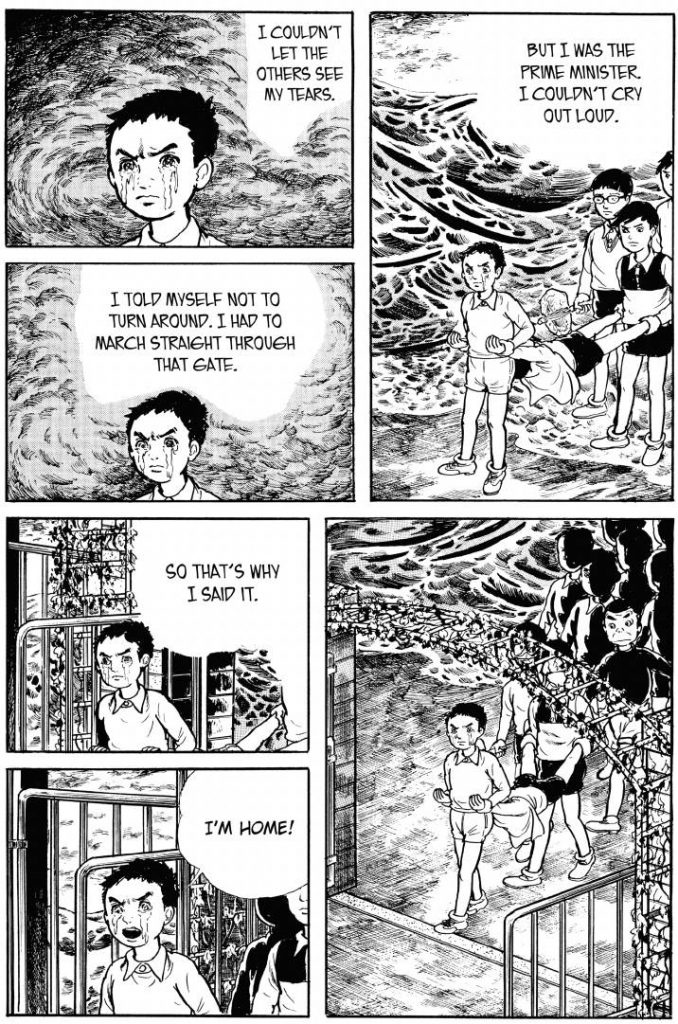

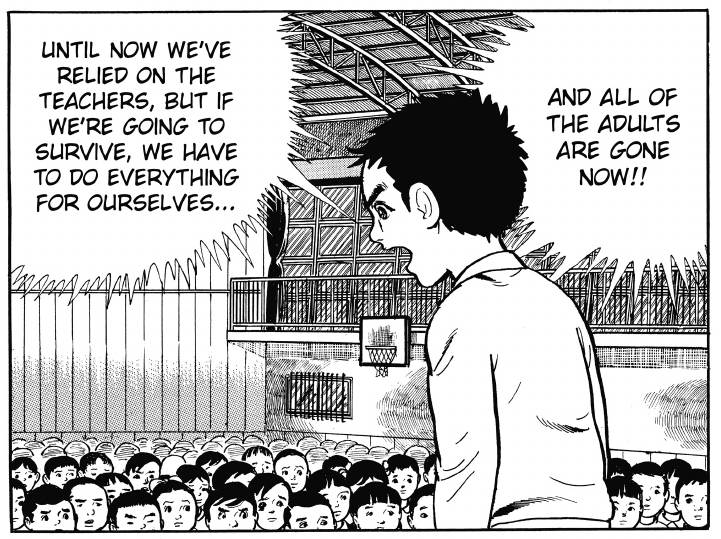

The story is told from the point of view of Sho Takamatsu, a twelve-year old sixth-grader who begins the story by getting into an argument with his mother before rushing off to school. The unresolved tension between the two play a significant role in events of the manga, and the narrative device is Sho’s diary in which he is talking to his mother. When the school disappears, it’s through his eyes that we see the horrors unfold. He jumps through the various stages of grief in the course of the first few chapters, and is one of the few that realize the kids have to maintain the peace both among themselves and among their juniors. It is not easy to steer this school of semi-hysterical children towards any kind of common action plan, but Sho does his best. From the very beginning, he takes on responsibilities beyond his age, calming the younger children down, taking charge of things when they spiral out of control.

The initial chapters of the manga capture the agonizing revelation that the survivors are well and truly alone, trapped in a world that is all desert and desolation, with the only resources available being the ones that are in the school compound. Umezu uses creative ways to dispose of the adult teachers, most of whom attempt to be the voice of reason as things go south. By the middle of the series, there is only one adult left, and he is in no mental condition to interfere. Having the teachers around in the initial chapters also demonstrates the freedoms inherent in the educational system in the seventies, namely, the ability to slap crying kids into silence.

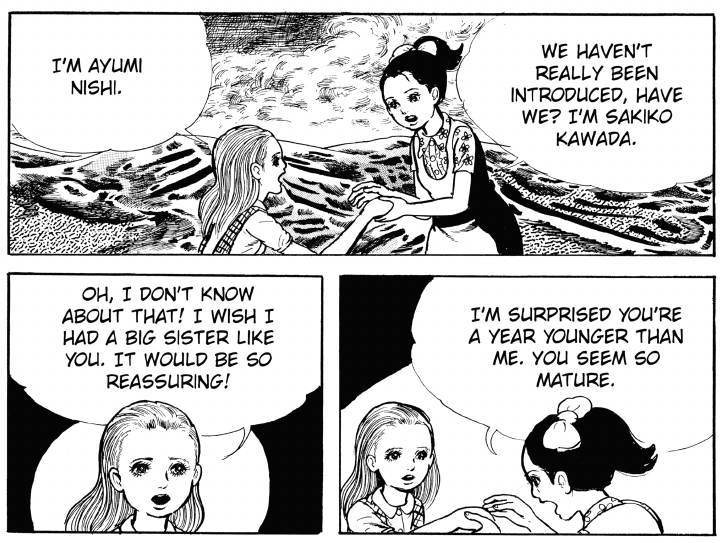

Umezu eases us into a cast of interesting supporting characters in subsequent arcs. There’s Saki, the level-headed girl who has a crush on Sho and therefore sides with him at all costs. The fifth grader Gamo looks like a scrawny nerd, and he is the brains of the gang, with the best ideas and theories whenever they are in a jam. Otomo, the class representative, starts the story as a member of Sho’s inner circle. Then there are the strange ones, like Nakata with the unquenchable appetite and hyperactive imagination, the handicapped girl Nishi, who struggles to keep up with the rest of the gang.

The challenges the kids face are unrelenting. The food delivery person takes over the cafeteria and keeps everyone away from what he considers his supplies. A particular teacher loses his marbles in a spectacular way. There is an outbreak of a deadly disease. Food and drinking water problems. Factions within the classrooms attempting coups and trying to rig elections. Blame-games and accusations related to who was responsible for causing the cataclysmic event, and the occasional ripple of superstition. A sudden rainstorm that threatens to destroy the school garden with a mudslide. A conflict that leads to an outbreak of fire. People unwilling to listen to reason. The school, as is to be expected, becomes a microcosm of society, and all burden of leadership falls on the shoulders of a bunch of twelve-year old children. And all these problems pale into insignificance when the supernatural elements creep in. A strange insect appears to consume some of the school-children, while leaving others unharmed. Ugly mushrooms grow everywhere, with no way to find out if they are edible or not, and those who consume them are….oh, now that is something you should read for yourself.

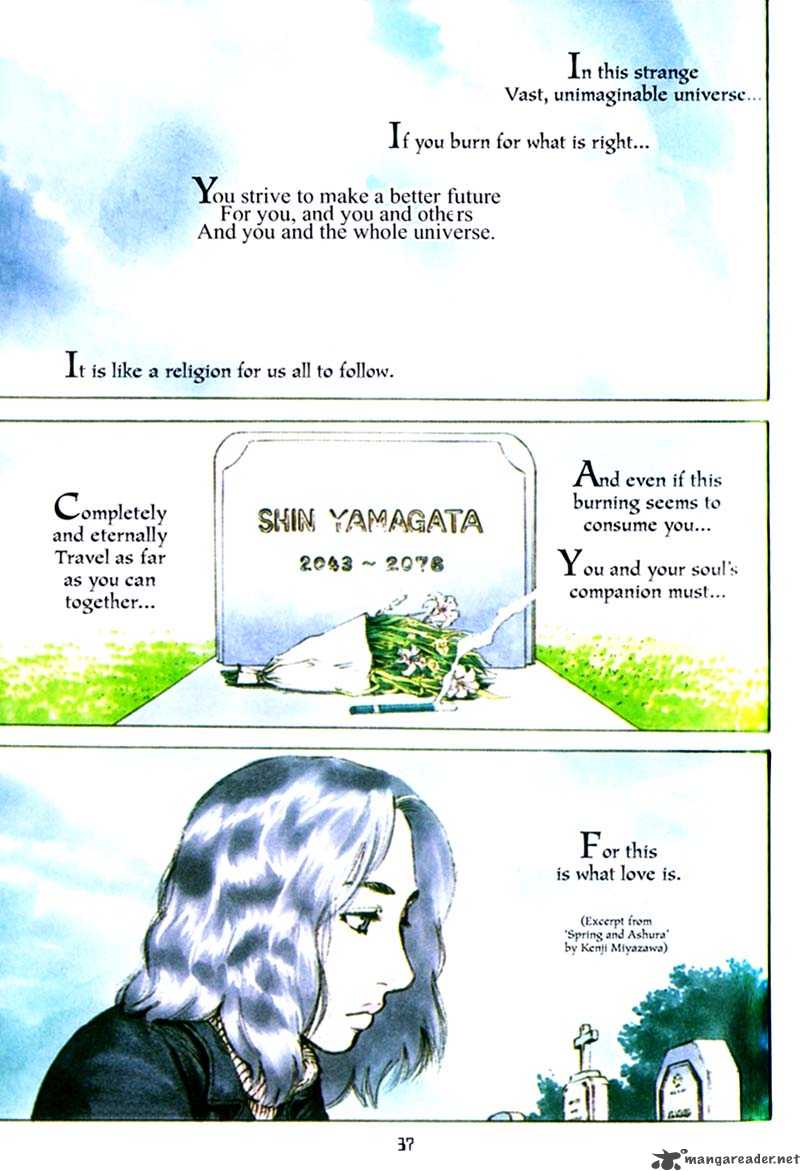

Very early on, the characters come to the realization that their displacement is actually a time-jump. They have arrived many years into the future, and in their original present, the school is considered to have been destroyed in an earthquake. This introduces a nifty semi-supernatural angle to the story, where Sho’s mother hears his voice in key moments of their struggle, and her actions in the past end up influencing the outcomes of events in the children’s future. This, incidentally, also leads in to the eventual climax at the end of the series.

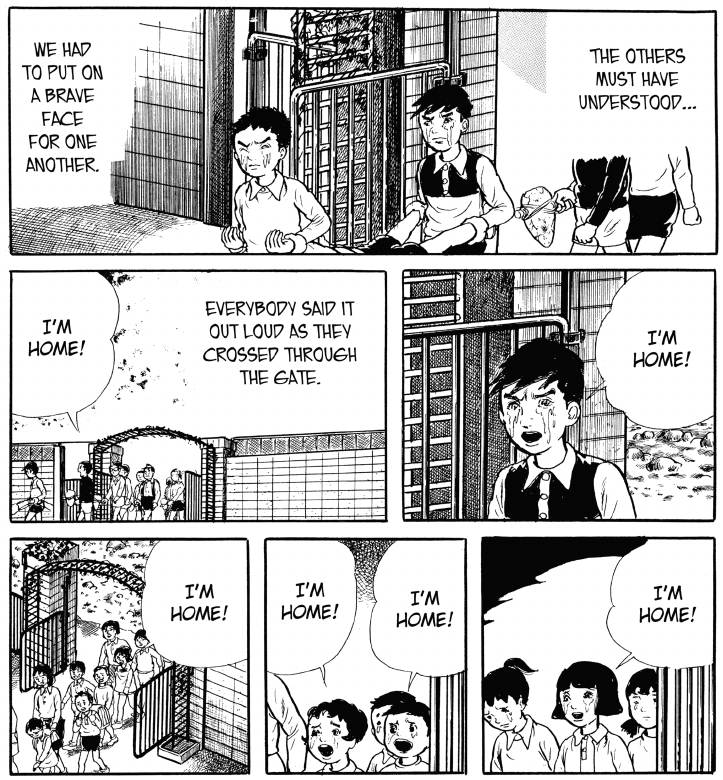

The sixth grade children agree to become the “parents” of the kids from the lower grades, with both the boys and the girls agreeing to carry out their responsibilities. This reads, and sounds both like social fantasy, and a reflection of the fact that it is the younger generation that think about and make sacrifices for the common good, and self-organize against existential threats. (shout-out to Greta Thunberg et al) No doubt some of this sounds very familiar if you have read Lord of the Flies, and the dozens of similar stories involving school-children stuck in mock societies bereft of adults.

Midway through the series, it is all but apparent that the story is an allegory for climate change. The desolate world the children are transported to is literally the future they inherit from a generation that has played havoc with nature. The explanation for how exactly the planet ends up this way fits in neatly with Umezu’s body-horror tics — grotesque tentacled creatures begin to appear, even as some of the students undergo physical changes because of their, ahem, dietary decisions. The fun is in seeing Umezu twist the knife even he guts the familiar tropes of the story. Like the best of horror stories, there is a tightrope between horror and absurd comedy that he excels at.

As the description suggests, there is a also vein of tragic madness that runs through the characters and their tribulations. Remember what I said about the heightened emotional pitch in Umezu’s writing and artwork? That is what makes the really dark turns of insanity among the characters distressing to the reader. When such a thing happens, when a character loses it, you do not realize at first whether it’s just the creator doing what he does best, or if it’s genuinely a character trait. It’s only when true horror comes lurching at us that we jerk back in our seats. By then it’s too late, both for us reading the story, and for the characters who bear the brunt of these breakdowns.

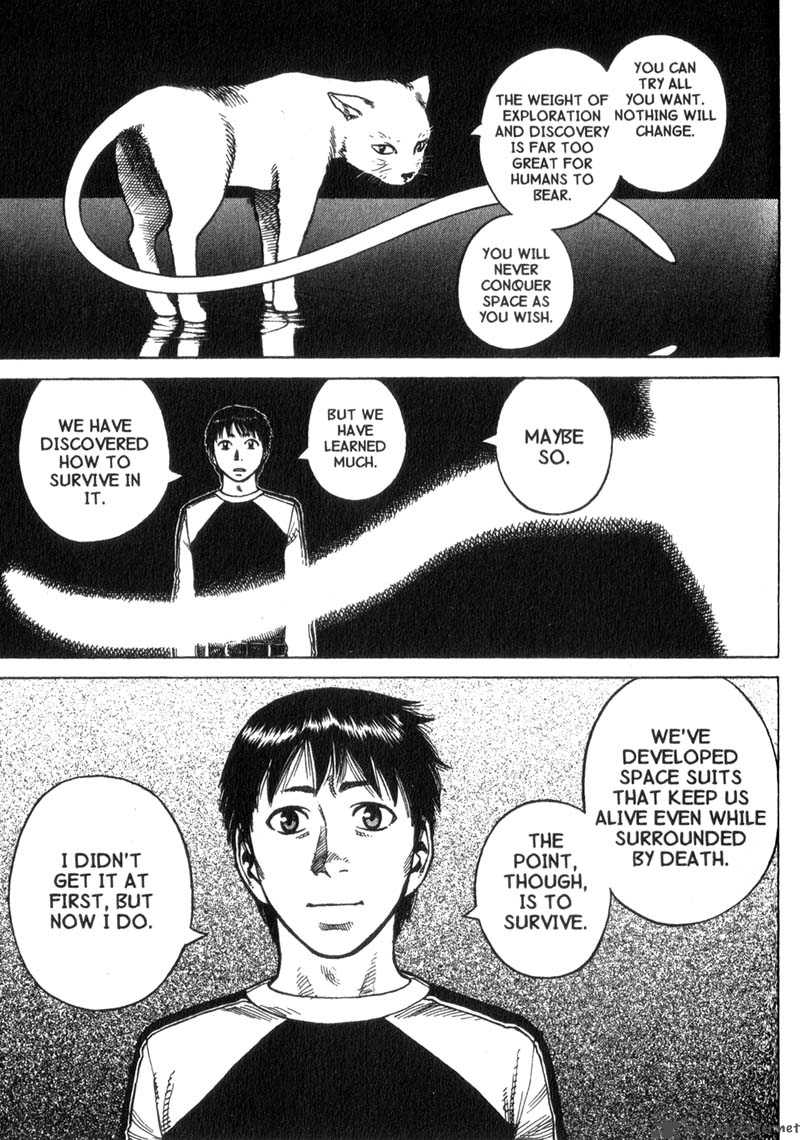

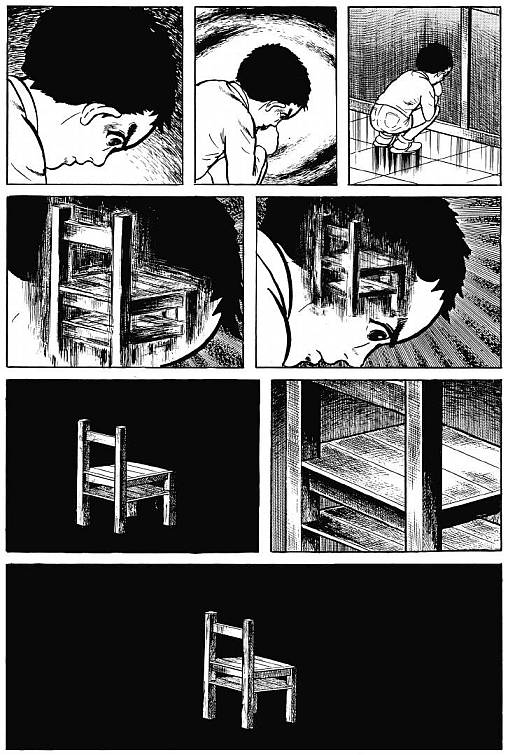

And of course, it goes without saying that Umezu is phenomenal at pacing and the art of the slow build-up. For all my scoffing about pitch, his mastery of layout and his ability to amplify childhood fears to a crescendo is in display throughout the book. Look at this example of a page where the kids have to hide from a monster. Gamo advises everybody to pretend to be an object to clear their minds of thought, since that is the only way to avoid being detected. “Become a thing,” he urges. A wordless page demonstrates Sho’s state of mind, even as the clock is ticking.

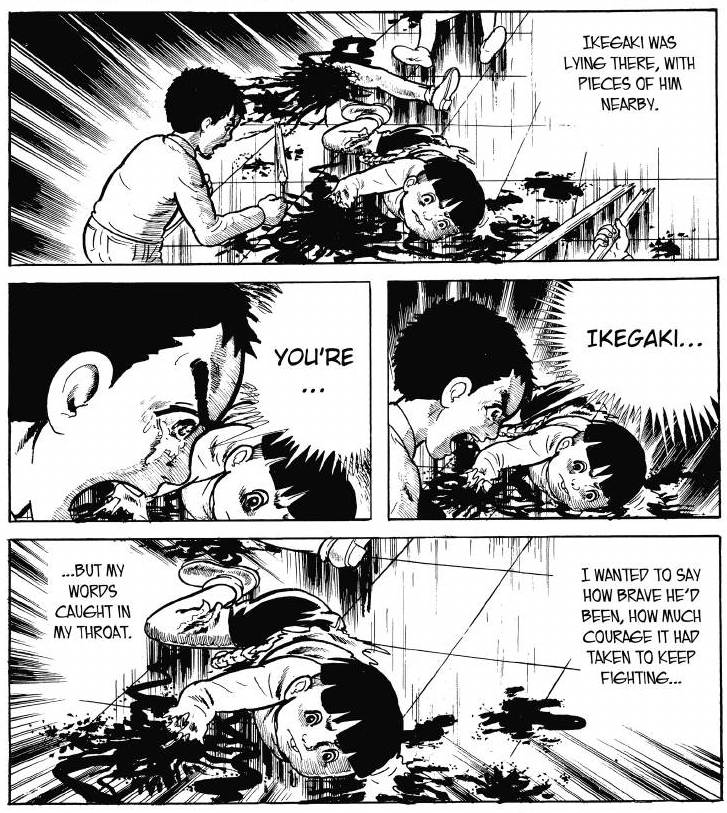

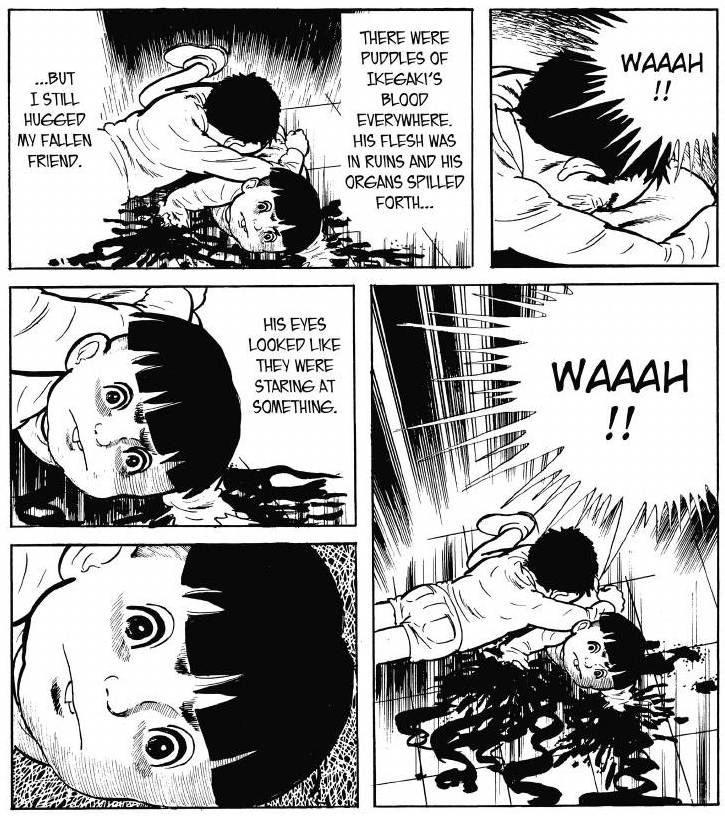

There are numbers thrown around in terms of student casualties as the book goes on, and let me warn you — the death toll gets higher and higher, and Umezu does not shy away from gruesome visuals. One of my favorite sequences is when the school is under attack by a giant insect, one that is seemingly unstoppable. Ikegaki, one of Sho’s classmates elected Minister of Defense, takes it on himself to organize the class scrappers to attack the monster as the others shelter behind barricades. They manage to turn the insect away, but not without casualties. The aftermath is brutal.

And that of course is one of the main reasons I still love well-written manga. The focus is not just on the grand moments, but also on what comes after. The sequence of panels slowly closing up on Ikegaki’s face make me tear up.

As the years go by, I have come to the conclusion that stories set in school hold great emotional resonance for me. Not because I have great memories of my school life, nor that I put myself in the shoes of a school-child when I am reading them. It’s possible that the combination of innocence and potential strikes a chord in me. Adulthood brings with it the jaded third-person perspective towards events in the lives of school children that are so earth-shaking for them. Umberto Eco wrote, “Life is about reliving your childhood in slow motion.” That may well be true, but I know I will never feel the bitterness of a high school rivalry, the pain of a crush on the girl sitting at the adjacent desk, the sheer terror of a teacher’s disapproving glare, at least not first-hand. Therein comes in my fascination with the school story, my way of vicariously living those myriad life experiences all over again. School is never a place one wants to be in as a child, but for some of us, it is a mental image of home, of a time and place where we were safe. And in a time when nothing and nowhere feels safe, isn’t it natural that I turn to school stories for succour?

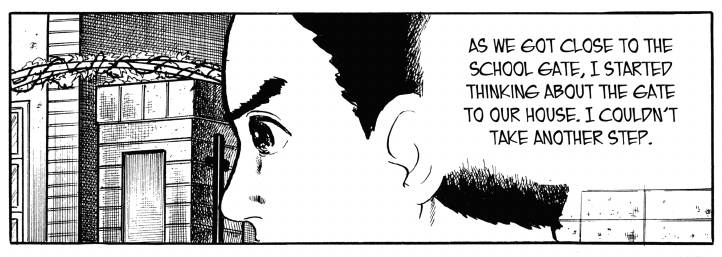

The school in the series represents a similar safe haven for the children. There is an emotional sequence around the middle, where Sho says “Tadaima” when he enters the school gates, back from an external expedition. The word, which means “I’m home” becomes a mantra for the children, all of whom begin to chant it as well, becoming a source of acceptance of the fact that they really have nowhere else to go. The Drifting Classroom, for all its perceived faults, is one of the finest school stories out there, and all you need to do is to switch off that irony-meter in your brain and give in to its charms. Despite the lump in your throat, you will find yourself cheering on the protagonists as, like the best of school stories, it ends on a hopeful note.