Have you ever walked out of a movie theater? I have. I walked out of Supari, once upon a decade ago, and I walked out after 30 minutes of that Vishal Bharadwaj film with Pankaj Kapur and Imran Khan whose name I cannot recall, it was that bad. Oh yes, Matru Ki Bijli. A screening of Profundo Rosso that was part of a double-feature, and it was so late in the night that my brain had turned to mush. I am fairly sure this number would have been higher had I not been with other people in the theater. Rajkumar Hirani’s PK, for example, and even the first Hobbit movie. In all these cases, I walked out because the films did not engage me in any way; there was some amount of revulsion involved, and the thought that if I did not allow more of my time to be wasted in that darkened theater, it would imply redemption of some sort.

Yesterday, I walked out of a theater for another reason altogether. It’s possible that in doing so, I startled the rest of the audience. I had been the first person to arrive at the theater, half an hour before showtime, and was able to pick the best seat in that sea of red faux-leather, that perfectly centered spot that brings the rectangular screen, uh, square in the center of your vision. There I sat, indulging myself in butter-covered food of the gods, acknowledging the matinee crowd that traipsed in slowly, film buffs, couples out on dates, parents with young children in tow, or the other way round. We laughed as the ads played, and the sounds of my chewing found sympathetic patterns in the mastication of other film-goers. The film trailers got over; the passive-aggressive switch-off-cellphone ads got some of us to double-check our devices, and we clapped as the theater darkened for the main feature. And once the movie began, it took me about 20 horrific seconds to realize what I was in for. To decide I did not want to see it anymore.

The movie was Mamoru Hosoda’s Boy and the Beast, and you see, the version playing on that particular screening was the one dubbed into English.

No. No no no no.

In my head, there is a clear breach of expectation that happens when I go to watch a film in one language and get another. It does not have to be Japanese anime; I have found myself cringing when listening to Pixar movies dubbed in Spanish, or even a Cantonese film in Mandarin. For anime, it hits me in the worst kind of way; the closest analogy I can give is when you go to a restaurant and order a plate of samosas. When the waiter brings the plate in, you smell the delicious samosa-smell and your mouth begins to water. The waiter has even remembered to bring chutney, and it’s the right kind of chutney, the syrupy, tangy tamarind recipe that goes perfectly with samosas. Eagerly, you pick up one of them. It is the perfect temperature too; freshly fried and kept aside for just the perfect amount of time that you know there will be no waiting for the filling to cool down, and that your tongue is safe. You dip the samosa in the tamarind chutney and bite into it. How would you feel if that samosa, for some reason, is sweet, instead of salty?

When the opening narration in the movie began in English, in my head, I was sure that there was A Problem, and only Swift Decisive Action could solve it. I remembered that I had double-checked to see if the matinee show had the original language or not, and the website said that only the 4 PM show would be dubbed. [ref]This had happened once before, you see, with a screening of a Ghibli movie, where but for an epiphany just before clicking the buy-button, I would have been sobbing through a dubbed movie after having taken a bus across town.[/ref] I could be that hero the rest of the audience needed. I ran outside, and the girl selling tickets was gone, and so was the manager, who had been lounging around reading a newspaper. There was only the guy selling popcorn, and he agreed with me, that the movie playing should be a subbed version. The manager came into view, finally, and he pointed out that Saturdays they only have two shows, and the 7 PM screening is when I would see the subbed version, if I wanted to come back. Unsure about my plans for the rest of the day, I got a refund. At 7 PM, however, I had come back. This time I did not buy the popcorn, and I made sure to ask about which language would play, before getting my ticket.

The movie? It was okay. Visually stunning, like Mamoru Hosoda films are. Hosoda and Makoto Shinkai are two anime film-makers who have distinct visual styles of storytelling. More importantly, their films contain stories with an emotional depth that other, more lackadaisical animation film-makers either glaze over or dumb down. This however has the fortunate (or unfortunate, depending on your point of view) of appending any discussion of the two film-makers’ work with a comparison to Hayao Miyazaki’s ouevre. I am guilty of making the same analogy when it comes to selling any of their work to my friends, to be honest. But here’s an admission — I think Hosoda and Shinkai, the latter in particular, bring in more emotional honesty and vulnerability into their work than Miyazaki ever did. Miyazaki protagonists are idealized archetypes, asexual and wide-eyed. These latter-day filmmakers make their characters more fragile and human, and that makes their work much more appealing to me.

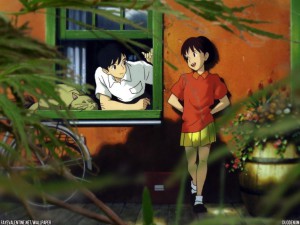

On the surface, Hosoda’s style is much more aligned with the aesthetics of Studio Ghibli — a little-known fact is that he was tapped to direct Howl’s Moving Castle, but Miyazaki took over due to creative differences. Much like the veteran film-maker, Hosoda’s work is rooted in Japanese tradition. Scenes from Wolf Children play out like extended homages to My Neighbor Totoro, and both Wolf and Summer Wars are as much about family ties and bonds with nature as any Ghibli movie you can think of. In Boy and The Beast, there are striking similarities to Spirited Away, especially with the concept of a parallel world that exists just beyond our world, and one human child that makes his way to the other side. There, Chihiro became Sen, with a flick of the characters in her name; here Ren becomes Kyuta because he is aged nine. There, our heroine was trapped in the land of the Others, who are unfamiliar and mostly horrific and unkind to trespassers; here, Kyuta willingly crosses over into a world of beasts who, though suspicious of the motives of the runaway human, mostly accept him in time. The theme of finding your family — blood or surrogate — loom large throughout the movie’s storyline, as does the idea of belonging.

My main issue is that most parts of the film feel rushed. It opens with a narrator explaining the situation, skimming through the world-building, telling us more than we can see. We never really understand certain characters’ motivations. There are too many montages — one where the characters go on a journey of self-discovery, for example, and meet a variety of powerful beasts in that world —no payoff to those scenes follow. Things get interesting when Kyuta begins his training under Kumatetsu, and the central theme of the film, that of these two unlike creatures finding themselves through each other, is cemented in this all-too-brief sequence. The third act falls apart almost completely, especially as grown-up Kyuta begins going back to the real world. Subplot brimming with threats and conflicts come out of nowhere, as do the resolutions; the romantic angle is all Jungle Book meets anime cliche, Ren’s meeting with his biological father is angst and adolescent fury, and the final boss-fight involves a character who is woefully under-explained. The only place, therefore, where Boy and The Beast really succeeds is in making us root for the titular characters right off the bat.

All in all, the movie suffers just because Hosoda’s previous work has been so good. Of course it’s a wonderful movie, full of wit and charm and moments, but it manages to not live up to expectations. But hey, this is from the guy that hated Howl’s Moving Castle the first time he saw it, and changed his mind later. If you get a chance to watch it, please do — and if you haven’t seen any of Hosoda’s previous work, check them out after this one.