TLDR: Best fantasy series I have read in the recent past, highly recommend.

So the Daevabad Trilogy caught my eye because of two main reasons:

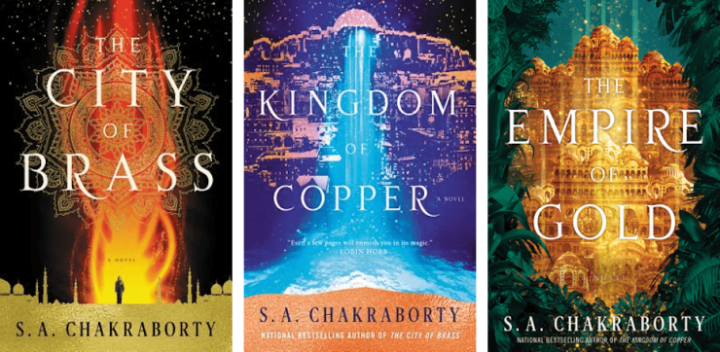

- The eye-catching cover of City of Brass, the first book, showcased in the fantasy section of nearly every local bookstore when it came out.

- The name of the author. SA Chakraborty is not only an Indian name, but is also a name from my part of the country. So I was curious, went and looked up the name, and found out that the writer was a New Yorker, and the initials stand for Shannon Ali. I didn’t think too much of it, other than a few mental tsks at the fact that obscuring the first names of women writers of fantasy for marketing purposes still seems to be a thing. (Don’t take my word for it – JK Rowling, NK Jemisin, VE Schwab are all part of the same club).

I did not read City of Brass right away, waiting it out because my queue was already backlogged. Plus, without any idea of how long the trilogy would take to complete, it didn’t make sense to plunge in and then wait for yet another Windy Winter. It was only when the second volume, Kingdom of Copper came out just about a year later, and to equally positive reviews, that I jumped on. A few days later, there I was, blinking at the last sentences of the epilogue to the second book, after a grueling sequence of mayhem, death, and heart-stopping action. “I’m home”, said the lead character, as tears sprang to her eyes. I was sitting in the courtyard of the public library next to my workplace, my lunch forgotten next to me, my skin breaking into goosebumps even though it was a sunny afternoon. I remember taking a deep breath, steeling myself to wait another year for the story to end. And then I sent a few texts to different corners of the globe, with the general message of “Drop everything and please read Daevabad trilogy”.

Empire of Gold, the third book, came out last month. Almost a year since I read the first two, and I realized I didn’t even have to refresh my memory, because the story had stayed with me. And when I was done, about twenty four hours later, there was the satisfied-yet-eager feeling that accompanies the best of endings. A good book is one that makes you miss the world, a magnificent book is one that encourages you to seek out even more. Empire of Gold jump-started my reading again this year, after a lag brought about by the quarantine period.

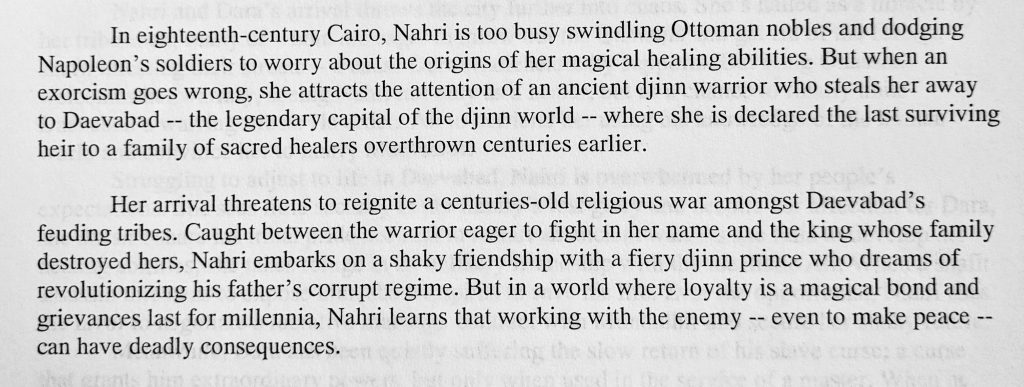

The Daevabad Trilogy is djinn-fiction set in the middle-east, in an opulent, magical city filled with magical beings that have complicated political and personal histories. Things happen when….wait, let the author herself set things up, instead of me blathering on.

A City and Its People

The city of Daevabad is described by the writer in such vivid detail that one wonders how much is her own creation and what bits existed in some forgotten manuscript, and of course it is the intriguing details of the city’s make-up and history that drive a majority of the tale. Turns out Chakraborty spent the better part of a decade poring over and creating these backstories before she began working on the actual book, as a sort of historical-fan-fiction-woven-with-fantasy project. It also helped that she was a history nerd, with a major in medieval Islamic history.

To appreciate the world of the books, it helps to know a bit of Islamic djinn canon. Djinns are fire elementals, capricious, endowed with superhuman powers, and yet human-like in the sense that they have children and may die, and as the books make it clear, they are immensely political. That the prophet-king Suleiman conquered the various races of djinns, stripped them of their magic and made believers of these capricious spirits is known. The ones who rebelled against Sulaiman’s rule were the ifrits, and they were forever banished. Suleiman gave his ring of sovereignty and the source of all djinn magic to Anahid, first of the Nahids of the tribe of Daevas, and the founder of the city of Daevabad.

Our ancestors spun a city out of magic—pure Daeva magic—to create a wonder unlike the world had ever seen. We pulled an island out of the depths of a marid-haunted lake and filled it with libraries and pleasure gardens. Winged lions flew over its skies and in its streets, our women and children walked in absolute safety.

https://www.sachakraborty.com/the-world-of-daevabad.html

The city is divided into various quarters, each populated by one of the six tribes that make up the djinn, and is ruled by the Qahtani family of the Geziri tribe. It is clear that there are undercurrents of hostility and mistrust among the various tribes, along with uneasy alliances, since the Qahtanis took power by force from the Nahids. Compounding all these issues is the presence of Shafits, half-human half-djinns who are allowed to live in their own separate quarters but with, shall we say, distinctly lower social status in this world.

It is into this unstable sociopolitical powder-keg that Nahri, our identifying character of the story, finds herself transported. Much like protagonists of other, familiar fantasy sagas, she finds her regular life and identity pulled away from beneath her feet, and most of the first book is her coming to terms with her mysterious connection to the Daevas since, as it turns out, she is a Nahid. Or maybe a shafit, we don’t know yet. Nahri’s priority is to figure out who she is and where she stands amidst the complex and contradicting options put before her, with nothing but her wits and street smarts about her.

“I wanted to find a balance between a starry-eyed dreamer and a ruthless pragmatist; someone who’s learned to temper her ambitions with realism and is largely okay with the moral ambiguities of doing what she needs to survive. I also wanted to explore the idea of someone being alone in a world that so strongly revolves around family and community.”

https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/sa-chakrabortys-the-city-of-brass-started-out-as-history-fan-fiction

As much as the story is about Nahri — and yes, I know, so far this sounds totally like a Chosen One on a Quest story, it is the supporting characters that make the book so, so much more. What helps here is that we are not just introduced to Daevabad from Nahri’s perspective, but also from within. The viewpoint of Alizayd Al-Qahtani, the younger son of the ruling king, one who is being trained to become the general to his elder brother Muntadhir when he eventually ascends the throne. His lens comes with the bias of being part of the ruling circle in the city and recognizing the injustices being perpetrated on the shafit. Ali is someone that is entrenched in the political system, both through his privileged bloodline and his training, and what he needs is to decide between his love for his family and his desire to see things change. When we first meet him, he seems to have made some choices that are going terribly wrong. And then things get worse.

Then there is Darayavahoush Al-Afshin. Dara for short. Once upon a time, Dara served the Nahids as one of their weapons of war, and his name has since become legend. He had disappeared for a long time due to reasons unknown, and his presence back in Daevabad, with Nahri in tow, causes jubilation in some quarters and terror in others. Things are further complicated by the fact that while transporting Nahri to the city, sparks fly between the two. And take my word for it, this is not a hurried, love-at-first-sight relationship. Half the first book is the journey undertaken by the two to reach the city, and they encounter friends and foes, and worse, each other’s idiosyncrasies on the way. The first kiss, when it happens, feels earned by both.

It would be unfair of me to reveal further of the plot, and besides, it is impossible to explain the complicated politics of Daevabad and the myriad subplots that weave throughout the story. A lot of reviewers have compared the series to George RR Martin’s A Game of Ice and Fire. To be honest, while the shallower aspects of Martin’s writing has seeped into a lot of fantasy, the comparison holds good here because of the way in which Chakraborty refuses to boil down her narrative into a straightforward good vs evil narrative. The main theme of the series is the complicated nature of relationships, both familial and of the heart. The secondary theme is the unforgiving nature of history, specifically the cycles of oppression and liberation that perpetuate across generations until someone decides to learn from them and, forgive me for this, “break the wheel”.

Spoiler-free list meant to titillate and intrigue, but will possibly be confusing:

- There are excellent curve-balls thrown into the story, involving not just the city and its djinns but the building blocks of grudges and betrayals that led to the present moment.

- We are introduced very early on to the earth and air elementals, ghouls and peris respectively. Later on, we meet the water elementals, the marids, first in a harrowing sequence involving Ali, and then in much greater detail in the third book. Its beautiful how all these different beings are woven into the main storyline.

- The second book jumps forward five years from the events of the first. The third book begins immediately after the cliffhanger epilogue of the second.

- There is a marriage of convenience. And broken hearts, broken promises, conspiracies and counter-conspiracies. Also, the family showdowns give a whole new meaning to the term “bound by blood”.

- For a while, I thought Ali and Muntadhir’s relationship mirrored that of Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh, and was on tenterhooks wondering if fiction would follow history.

- There are various points of the story where the characters are placed in positions of convenience, where they could have said “fuck it” and let things be, choosing to be beholden to the status quo. But of course, it’s their choices that drive the story. I loved that.

- Dara is added as a point of view character from the second book onwards, and suddenly it makes so much sense. It’s also heartbreaking to both identify with his impulses and to understand how he is pulled into events that spiral beyond his control.

- Pay close attention to Nahri’s personality – her reactions to events telegraph what she wants, and also what she needs. She gets the former at the end of the second book, and she has to work to earn the latter in the third.

So. Much. Love.

There are so many reasons why I love this trilogy so much. I was burnt out on SFF for quite a while, mostly because the tropes were getting tiresome, and there are only so many variants of Chosen Ones on a Quest to defeat a Dark Lord that one can take in without feeling wiped out. Hard fantasy also has had this tendency to force the reader into doing homework, trying to figure out milieu and context through maps, linguistic tongue-twisters, and a whole bunch of expository text referred to as “world building”. Dragons, witches, elves and dwarfs are de rigeur, as are pseudo-European medieval feudal kingdom settings.

Obviously, for me, it’s the joy of seeing characters and settings that do not fall in that narrow band that has dominated fantasy all throughout. It is not as if djinns have not appeared in Western fantasy at all, but those appearances have primarily been through a first world filter. The “genie” in this setting is a fast-talking trickster figure that grants wishes, and then chooses to side with the protagonist, becoming a secondary character in the hero’s quest. I am thinking of the titles that come to mind – The Thief of Baghdad, Disney’s Aladdin, I Dream of Jeannie, The Bartimaeus Trilogy, only the last of which has any motivation to go beyond the surface level tropes associated with these beings. Of late, of course, there has been better works – Helen Wecker’s Golem and the Jinni comes to mind, but even that is set in early 20th century New York, with brief flashbacks to a far-flung past.

So unlike the Eurocentric fount of stories, it’s refreshing to see a world inspired by stories of court intrigues set during the Abbasid Caliphate.

For one, the period I particularly enjoy—the Abbasid Caliphate—was in many ways a bridge between the ancient world and the more “modern” medieval era, witnessing an incredible syncretism of different cultures, languages, religions, and customs. I like seeing the way places and people change: that a proudly Arab Muslim court might be modeled on a Persian Zoroastrian one, led by a wazir whose family had been Buddhist priests centuries earlier, and that it would have employed Greek scholars and Hindu surgeons and sent trade missions to China. I don’t have any illusions that this was always peaceful, but these were teeming, fascinating, and diverse cosmopolitan cities.

https://www.lightspeedmagazine.com/nonfiction/interview-sa-chakraborty/

To be clear, Chakraborty is not the only Muslim writer with spins on Islamic folklore. Names I can think of include Saad Z Hussain (his The Gurkha and The Lord of Tuesday is short but beautiful, and Djinn City is on my list), Sami Shah’s Fire Boy is set in Karachi, while G Willow Wilson’s Alif The Unseen brings together djinns and cyberpunk, two genres I never thought of seeing together. And of course, I should not forget Salman Rushdie’s Two Years Eight Months and Twenty Eight Nights, which is the closest to superhero djinn fiction I have ever read.

The characters and their arcs, and by this I mean not just the three main characters I mention, but the ever-widening supporting cast that Chakraborty situates around the protagonists. It helps that the names are beyond fabulous — who can help but swoon at names like Muntadhir, Zaynab, Manizheh, Irtemiz, Mardoniye, to name a few. There are even Bangla names thrown in (Subhashini and Parimal Sen, and it warms my heart to see the former spelt the proper Bengali way). The homework part of reading fantasy automatically goes away, since these names are not only culturally familiar to me, but also rooted in a classical tradition instead of being made-up fantasy tongue twisters. The nomenclature of the world is a confluence of Persian, Arabic, and Indian cultures, and you would be hard-pressed to pinpoint the differences.

As much as it feels like obligatory love triangle is telegraphed with two male and one female lead characters, the beauty of these books is how it subverts those expectations. It is clear that a lot of thought went into the individual motivations of each character, and Chakraborty recently talked in a Reddit AMA about how she wanted her main character to go through different shades of love—infatuation, sexual experience, trust and mutual respect, while also becoming better people. The Quest therefore is not just a tagline or a MacGuffin; finding a magic sword or defeating an Evil Lord could be the endgame in a different unending war, but for Nahri, Dara, and Ali, it is all about finding themselves, owning up to and healing the pitfalls and mistakes of the past. The series does not end with a grand flourish of hashtag winning; it awakens to another day in the life of the city where change is in the air, and they who remain need to get to work.

Final note about how immersive the story was. I read the books on my Kindle, and as I was in the middle of Kingdom of Copper, I realized around lunchtime, with a shock, that the Kindle had run out of charge at a crucial point. I ran to the library next door, hoping that there would be a copy left. No luck. In a final act of desperation, before giving up completely, I searched the library app to see if they had an e-version I could read on my phone. Whaddya know, Hoopla had the audio-version. So I scrubbed the audio all the way to the correct chapter which, on a phone, is madness. And I spent 45 minutes listening to Soneela Nankani narrating the story, only half-wincing at the rolling r’s in her pronunciations of Nahri and Dara. But there you go, that’s how much it hooked me. And hopefully will do the same to you.