Once upon a time, a decade and a half ago, to be precise, I was introduced to the work of composer Yoko Kanno, and spent endless hours swimming in her music. The soundtrack to Cowboy Bebop was one of the foundational albums of my life. It became not only as my favorite anime OST album of all time, but was high on the list of genre-bending musical works that have inspired me to keep looking for, and appreciating, new music. (Other names in that list, you ask? The OST of Kill Bill. Gangs of Wasseypur. Dev-D. Susheela Raman’s Love Trap.) Oh, lookit, I used to rave about her music so much, back in the day.

Yoko Kanno’s music never really faded from my life, but like other artistes I enjoy and have heard in depth, I would return to the fountain of her album with delicate steps, drinking lightly, trying not to let the taste get too over-familiar. There is a joy to traversing half-forgotten pathways in your brain, when you find yourself being able to anticipate the harkat in an instrumental solo milliseconds before the fact, or when your body tenses at the aneurysm-inducing chorus that is about to hit. It also helped that her music, specifically the Cowboy Bebop OST was not on Spotify, my music application of choice.

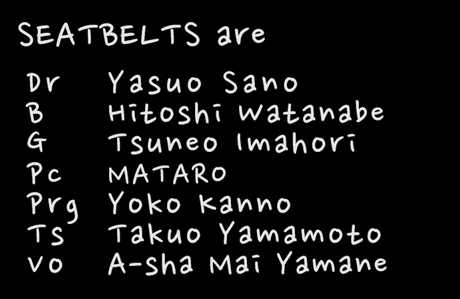

That changed in July this year, when all the Seatbelts’ (which is the name of the band that Kanno got together to produce the Bebop OST) work was finally up on Spotify. Here are the complete albums, all seven of them in a single playlist.

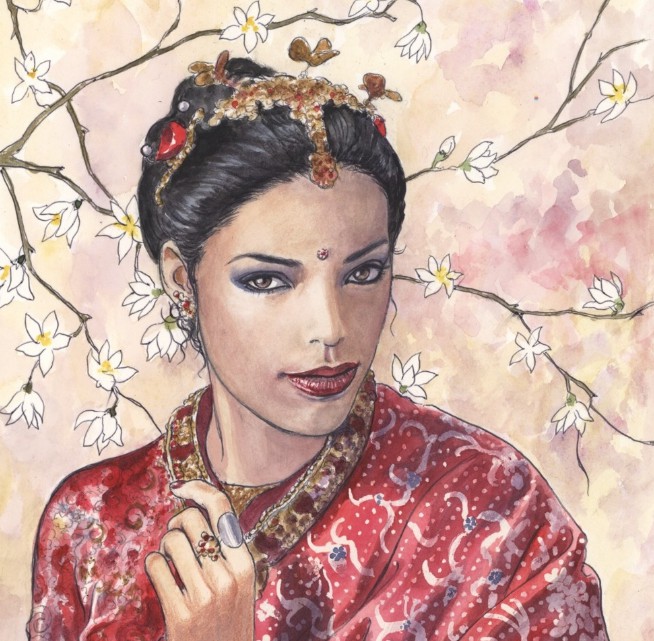

But the intersection of Cowboy Bebop and 2020 began before that, with the Seatbelts getting together on Youtube to produce a set of live virtual sessions for charity, called the Starduck Sessions. Yoko Kanno makes special appearances in them, a dancing shadow on ‘Tank’, person sleeping in bathtub on ‘Lion Sleeping’, helmet-wearing pianist in ‘Space Lion’. A particular favorite is the smoky, intimate version of ‘Real Folk Blues’ by Mai Yamane, stripped down to voice, guitar, and bass. All eight videos are here. I swear I blinked back tears at ‘Space Lion’, all over again.

But that was not just it. You see, during the pandemic, a bunch of musicians, with the blessing of Sunrise, the original producers of Cowboy Bebop, and Funimation, the US distributors, produced a virtual session of “The Real Folk Blues”.

The musicians really take it to the next level, especially the combination of singers Shihori and Uyanga Bold, along with guest vocalists Raj Ramayya (one of the voices on both the Bebop movie and OST). The list of musicians is staggering, as is the production quality. The main vocalists do their thing with the original Japanese lyrics, alternating lines among themselves, while the chorus goes into overdrive with a bunch of backing vocalists. Listen to how Uyanga jams with the saxophone at 2:56.

The fun begins when the original song ends. That’s when three rappers get in and add their layers of poetry as the music continues. While the performance in and of itself was enough to get my nerd juices flowing, it’s the appearance of the original Seatbelts line-up in this final part that got me teary-eyed again. Look, there’s Ms Kanno too, being weird and cute and so full of all the coolness. Mai Yamane says hello too.

The full lineup of musicians, from the Youtube description.Mix / Additional Guitar: Masahiro Aoki (Legendary former composer at Capcom with credits on Megaman, Street Fighter V, Astral Chain, and more)

Organ: Robbie Benson (Band leader, Super Soul Bros)

Keys: Ed Goldfarb (Series Composer, Pokémon: The Animated Series)

Guitar: David McLean (Guitarist on Beyblade Burst, One Minute Melee, host of Animyze)

Synth/Additional Sound Design: Jason Walsh (Senior composer and sound designer at Hexany Audio with recent credits including Overwatch Contenders, PUBG Mobile, and League of Legends)

Bass: Matthew Hines (Touring bassist with recent gigs including the Jonas Brothers, Ledisi, Summer Walker, Kiana Lede, Bazzi, and more)

Drums: Kevin Brown (Touring drummer with recent gigs including Jason Hawk Harris, the Southern California Brass Consortium, and more)

Saxophone: Zac Zinger (Composer and woodwind player for Street Fighter V, Jump Force, Mobile Suit Gundam: Side stories, and more)

Flute: Kevin Penkin (Series composer, Made in Abyss, Rising of the Shield Hero, more)

Lead Vox 1: Shihori (J-pop singer and song-writer on shows like Fairy Tail, Macross Frontier, Irregular at Magic Highschool, and more.)

Lead Vox 2: Úyanga Bold (Lead vocals on things like Mulan (2020), League of Legends, and multiple projects with Hans Zimmer/Pinar Toprak etc.)

Lead Vox 3: Raj Ramayya (Lead vocals on Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, Wolf’s Rain, Made in Abyss, and more)

Backing Vox 1: Dale North (Composer for Dreamscaper, Wizard of Legend, Sparklight, Nintendo Minute, and more)

Backing Vox 2: Dawn M. Bennett (Voice actress for anime and game series like Dragon Ball Super, Fairy Tail, RWBY, Borderlands 3, and more)

Backing Vox 3: Kaitlyn Fae (Filipino-American singer, actor, writer, director, co-host on the nerd video podcast, PanGeekery)

Rap 1: Substantial (Legendary jazz-hop rapper, Nujabes’ collaborator, with dozens of major placements and projects)

Rap 2: Mega Ran (Critically-acclaimed nerdcore legend)

Rap 3: Red Rapper AKA Zaid Tabani (Rapper with credits on Street Fighter, the EVO worldwide fighting tournament’s main theme, and Rooster Teeth’s Red VS. Blue)

Poem: D.B. Cooper (Voice Actress and director on Hearthstone, Bioshock 2, The Amazing Spiderman 2, Ghostbusters (2016), DC Universe Online, and more)

Spoken word: Beau Billingslea (Voice actor from Cowboy Bebop – Jet Black)

Ending Tag: Steve Blum (Voice actor from Cowboy Bebop – Spike Spiegel)

String Director/String Arranger/Orchestrator/Disco slide king: Lance Treviño (Film composer for titles like Beyblade Burst God, Hanazuki, Chef’s Table, and more!)

String Copyist/Orchestrator/String Mockup: Dallas Crane (Multimedia composer and personal assistant to Austin Wintory)

Strings: Our string section is composed of brilliant artists whose individual credits include grammy nominations, tours with artists like Eminem, Sting, and Hans Zimmer, and recordings for soundtracks like Steven Universe, God of War, The Lion King (2019), and many, many more.

Violins – Molly Rogers, David Morales Boroff, Felicia Rojas, Jeff Ball

Violas – Joe Chen, Molly Rogers, Isaac Schutz, Jeff Ball

Cellos – Andrew Dunn, David Tangney

Upright Bass – Travis Kindred

After all the tears had fallen, it was time for me to go back to basics, and re-watch the series and the movie. 20 episodes in, and I can’t get over how timeless Cowboy Bebop remains. ‘Asteroid Blues’ is the episode I must have seen at least 20 times in 3 years, giving friends the initial hit of the show. ‘Jamming With Edward’ and ‘Mushroom Samba’ still get me laughing hysterically. The poignant episodes with Faye and Jet still hit that perfect note of melancholy and wonder. The boy from seventeen years ago would approve, I think.

Footnotes

- Guess what, The Yoko Kanno Project is still online, a rarity in a world of rapidly decaying links from two decades ago.

- I never knew that the character of Ed was based on Kanno herself, according to director Shinichiro Watanabe. I found that out a few days ago.

- Of course, it’s but natural that after watching Bebop, I will be jumping on Samurai Champloo, followed by Kids on the Slope, both of which I have seen before. It’s Watanabe’s newer ouevre that I haven’t seen, including Terror In Resonance and Carole and Tuesday. To be remedied soon.