This post has been in my drafts for ages. I was trying to get citations on certain facts, but that would have required months of burrowing through old issues of Filmfare and Stardust magazines and time, which I don’t really have. It’s sad and strange that the Internet does not remember PK Mishra anymore, even though his songs ruled the airwaves back in the day. If you have any more PK Mishra facts, including what his real name was, anything at all, hit me up. He needs a Wikipedia page at least. I want us to not forget.

You are a poet from Rajasthan, and you have been trying to break into the film industry for a while. Out of the blue, you get a call. You have been employed to write the lyrics for songs in a new movie. The director is well-known in his field, and the composer is new to the game, no baggage, zero ego. You feel a thrill as you go in to your first session. Song-writing for Indian films is all about creating words and music based on a situation, a feeling, a bend in the road, an ode to the vagaries of life, and you are eager and curious to see what’s in store for you.

But what is this? You are told that the songs have already been written, in a different language, and you actually have to translate it into Hindi. Harsh, but what to do? You know the original language, so it’s not all that bad. It’s all about coming up with rhymes and verses in your mother tongue. You can roll with that, you say, and get to it.

Except there is a hitch. You cannot just translate as is, you see. The actors in the film have already shot the visuals in a different language, and you have to ensure that their lips sync with the new words as well. “What do you mean?”, you ask. “They are singing in a different language.” “Er, no, ” you are told. “They have to seem like they are singing in Hindi.” Well, fine, it’s a constraint. But you are an artist and you understand constraints, so you go about and do your job. You have to pay attention to the visuals, so that you understand at what points of the song you see lips moving, and others where you can get away with playing fast and loose. “Asha” and “Aasai” sound about the same, so that’s easy.

Another hitch. You see, the composer and director both insist that certain words have to stay the same. They match the mood perfectly, and even though they do not have any meaning per se, those words need to be around. “MTV generation, sir. Youth, sir,” you are told. “They need to latch on to something catchy, otherwise how can they remember the song?” You don’t really understand, because you saw the movie and there’s no one named ‘Rukkumani’ in it, and you try to bring up the fact that the North Indian version of the name should probably be ‘Rukmini’, but no one cares. So you shrug and you do your best.

Yet another request. There is this song , a full-blooded, goose-bump inducing song about how great….Tamil Nadu is. But the rest of India wouldn’t care, so you need to talk about the country instead. The good thing is, there is no lip-synced video, so you can go wild, and you do.

So Roja comes out, and the songs, your words accompanying them, go stratospheric. Never mind the fact that they got your name wrong on the cassette cover. Your name is not PK Mishra, they called you Mishra-ji when you came in every day, and they forgot to ask you what your first name was. When they couldn’t find you, some wit decided to put PK in there, since you came in to work a little tipsy, every now and then. Ha ha, really funny. But none of it matters, because they love the music, and those songs you wrote, they are playing on the radio, and even on Chitrahaar.

People are talking about AR Rahman, the new wonder kid from Madras, and every now and then, somebody even talks about you. But mostly, they laugh at how saucy that Rukmani song is, even though you thought it was tame by what your peers were putting forward in Hindi cinema at the time. The kid ends up winning a bunch of awards, as does the lyricist for the original songs. Nobody pays much attention to your work. After all, what you did was nothing original, anybody can translate words from one language to another, right?

But yet, it turns out that you make this a steady career. You fit a niche. There is opportunity to be seen for every producer that wants the pan-Indian market, and you are the go-to guy when it comes to transliteralipsyncizing songs into Hindi. You accede to every demand, and you do your best to play by the rules. You take it easy, as a matter of policy. Other lyricists would have run screaming for the hills if asked to write a rap song that talks about localities in Chennai, one that makes use of local references, puns, and tongue-twisters, but you gamely take on the challenge, transposing it to a different audience. For some songs, you put in the exact English words they want in the verses. Well, except for that time you thought nobody up North cared about Elizabeth Taylor so you put Madonna in there instead, but hey, it went well. You don’t bat an eyelid when they ask you to take on songs that swim in alliteration and onomatopoeia; if it’s possible in Tamil, you will find a way, any way, to get a Hindi version. You become flexible with meaning sometimes, when a song about the Goddess Kali becomes one about being the Prince of Delhi. Despite your lyrics being burdened with the broken accents of singers unaccustomed to Hindi.

The strange thing is, when given creative freedom with your translations, you go above and beyond. I look at your translated version of songs that were remade with different actors (oh yes, that was a thing too, later in the nineties) and they are so different from the ones where you need to adhere to specific imagery from the original Tamil version. You also made the best of the leeway from tracks that do not involve lip-syncing. Also interesting are the translation choices you make, like taking a song that’s about the daughters of various people in a village (can’t even) and make it one with actual women’s names. A song about a flower blooming to the touch becomes one about falling in love, but just a little. (What does that even mean, we wondered, to have thoda thoda pyaar, as opposed to dher saara pyaar? But that was you playing around with the Tamil words “thodath thoda” and picking the word transposition of least resistance. The meaningless word “Kulivalile“, shoehorned into the visuals of a film just because the composer and lyricist couldn’t think of a better word, to you that word became “Phoolwaali ne“. I don’t know whether to laugh or just be in awe of your creativity every time I hear the Hindi version.

But tell me, Mishra-ji, was there ever this feeling in the recesses of your mind, that all your work, the kind of ideas and effort you put into unraveling the cultural Gordian knot of North and South, all of it was temporary? That by transferring near-verbatim the flavor of one end of the country, you relinquished some of the ownership that comes with pure art. I am into comics, and there is this recurring joke in that field about inkers. The punchline is that inkers are not real artists, that they just trace the penciller’s work. I see that similar argument made about your contributions to Indian cinema, and pardon my language, that is such bullshit.

Maybe you realized that there will come a time when there is more money to be made in remaking films outright, using a different creative team. Perhaps you suspected that, had you continued work in purely dubbed films, you would become a relic, and those colleagues and patrons that offering you a steady assembly-line of work will switch off the lights and walk away anytime the money dried up. There were songs you were clearly phoning in, employing the bare-minimum effort to string coherent lines together.

By 1997, the writing was on the wall. Others had taken your place in the corridors of Panchathan Record Inn. You branched out among other music composers of the South. Your oeuvre included names like MM Kreem and Deva and Illayaraja, you bringing their tunes to a different market, just as you brought Rahman’s. It was interesting to see you branch off into doing original Hindi and non-Hindi films. Your work with director Mani Shankar, in particular, stemming from your collaborations with Karthik Raja. You did not burn up the charts or the box office with those, but they remain worthy snapshots of your career.

My personal favorite of your non-Rahman career however is this all-but-forgotten album called Meri Jaan Hindustaan, released in 1997, the same year ARR’s Vande Mataram appeared, with lyrics by your spiritual successor Mehboob. Pop patriotism was at a fever pitch, that fiftieth year of our independence, and one cannot fault you for climbing aboard that money train. But what a product, sir ji. Your song for Lucky Ali, ‘Anjaani Rahon Mein’, remains the most famous of them all, still accessible on YouTube. But there are others I find worthy of both mention and memory. This Chitra and MM Kreem duet called ‘Kho Jaane Do’, which had Deepti Bhatnagar and Rani Jeyaraj in the video. Karthik Raja’s ‘Sehra Baandh Ke Nikle’, a strange, almost atonal ditty punctuated with a rap section that you wrote. I have never managed to find out if you wrote the Baba Sehgal number “Howzzatt”, or the Illayaraja track with Kamal Haasan vocals ‘Apna Josh Hai’. I wouldn’t be surprised if it were so.

It is 2020, Mishraji, twenty eight years since you first brought a nation together with your words. I was a twelve year old boy in Assam when I saw your name on that cassette cover, and for the next couple of years, seeing your name on a byline made me wince and celebrate all at once. Because I did not know what to expect, and believe me, that is not a bad thing. Your words are seared in my brain, and come back to me in the strangest of moments, like when I am outside and there’s a bus across the street, I half-expect a man in red socks to come flying out the window and begin thrusting his pelvis gloriously at the world. The words accompanying the song in my head are like confused bursts of radio static, and go from Tamil to Telugu to Hindi, and of course, your words are the ones I really understand, even though it’s the other languages I mouth along. I envied the lucky folks who had access to Tamil releases, but your work helped relieve some of that FOMO. A phrase that did not even exist back then, but the feeling did, believe me.

The words you strung together felt so random sometimes, and yet when I listened closer to the Tamil versions, and pore over online translations, I realized you were not the one rhyming “sensation” with “temptation”, nor were you the one with the fishing net metaphors. You were however wholly responsible for the evocative phrase “baadal tirikit tirikit bole“.

Despite being good at your professional career and a symbol of change, you are barely a footnote to that decade of musical upheaval. Your words have now become samples of memetic derision among those that sigh over the poetry of Hindi film music. AR Rahman has always maintained a studied distance from your existence, and would rather not consider the pre-Rangeela years of his dubbed catalog as canon. Your namesake turns up when I look for you online, a gentleman associated with the current political party. There are one or two articles about your death in 2008, with the vaguest of allusions to your life other than what we already know. There is not even a picture of you available anywhere. No interviews, even though I scrounge through a multitude of YouTube channels that trade in vintage film videos. What I have figured out is that you came from Sujangarh, Rajasthan, and that you lived in Chennai for the major part of your life, and that you knew Tamil well. Or you must have. I wonder how and why you made it to the Madras film industry, of all places. There is not even a Wikipedia page for you, sir, and I have thought very hard about how I can create one. But alas, without citations and online paraphernalia, it is impossible to categorize you as a “person of note”.

And it’s sad, Mishraji, that your work does not get the sort of appreciation that it should. Without you, there wouldn’t be this cross-pollination of North and South that defined Indian film music of the nineties. At least, it wouldn’t have happened this early. You had created a path for others that followed, people with more clout who could insist on a little more respect for lyrics and their translation, getting producers to pay up for re-shoots so that the constraints on their words were loosened. You did not have that luxury, but you delivered without complaint or drama, with professional courtesy, not letting your ego get in the way of a director’s vision or a composer’s idiosyncrasy.

What remain with me are memories of conversations I have seen on random channels at random times of my life. How you proudly spoke about changing the main lyrics of Dalapathi to something more palatable in Hindi, than the exact translation that you were asked for (“Aye ladki, chutki bajaa” just didn’t have that zing, you said. ) How you felt forever cheated because they got your first name wrong on the cassette of Roja and you were stuck with it for the rest of your career – and life. And I can see you chuckling over not using “the ship of friendship” in your translation, because it just wouldn’t work in the song.

You have popped up the most random of places when I went hunting for you – is that really your voice on the Akshay Kumar version of Jhoole Jhoole Lal, from that smelly turd that is Jai Kishen? IMDB seems to think so. Your name also comes up as composer for Sapna Avasthi’s album Pardesiya.

The one question I would have liked to ask you, though, is this. Were you doing this because no one else would, or did you really enjoy it all? I would like to believe it was the latter. I would like to think that there is no way you could come up with a phrase that goes “flexible like a noodle” without chuckling to yourself, and weren’t indulging in your drink of choice when rhyming “Glaxo baby” with “BP”. Your lyrics, sir, remain among the most fun experiences of my adolescence and a pleasure (and sometimes, a pain) to revisit. Is there anyone else who will match your chutzpah when it comes to visual poetry? There is no muqabla, subhanallah.

An Incomplete PK Mishra Discography

| Roja | Tamil | Roja | AR Rahman |

| Dharam Yodha | Malayalam | Yodha | AR Rahman |

| Muthu Maharaja | Tamil | Muthu | AR Rahman |

| Tu Hi Mera Dil | Tamil | Duet | AR Rahman |

| Vishwavidhaata | Tamil | Pudhiya Mugam | AR Rahman |

| Humse Hai Muqabla | Tamil | Kaadhalan | AR Rahman |

| Chor Chor | Tamil | Thiruda Thiruda | AR Rahman |

| Priyanka | Tamil | Indira | AR Rahman |

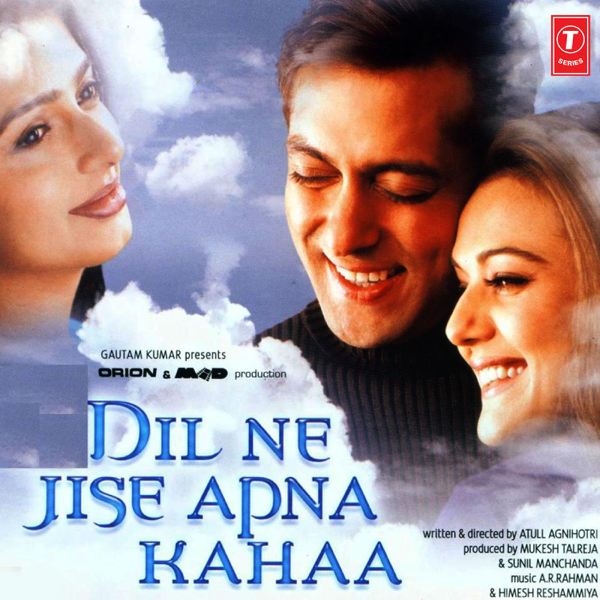

| Love Birds | Tamil | Love Birds | AR Rahman |

| Hindustani | Tamil | Indian | AR Rahman |

| Duniya Dilwalon Ki | Tamil | Kaadhal Desam | AR Rahman |

| Mr Romeo | Tamil | Mr Romeo | AR Rahman |

| Aaj Ka Romeo | Tamil | Indhu | Deva |

| Dalpati | Tamil | Dalapathy | Illayaraja |

| Sazaa-e-Kaalapani | Malayalam | Kaalapani | Illayaraja |

| Grahan | Hindi | Original movie | Karthik Raja |

| Chhalia | Tamil | Raasaiyya | Illayaraja |

| Meri Jaan Hindustaan | Hindi | Original Album | MM Kreem/various |

| Pardesiya | Hindi | Original Album | PK Mishra |

| Naya Jigar | Telugu | Snehamante Idera | MM Kreem |

| Govinda Govinda | Telugu | Govinda Govinda | |

| Mitr My Friend | B Illayaraja | ||

| The Smart Hunt | Tamil | Vettaiyadu Villayadu | Harris Jayaraj |

| Coffee Aur Kreem | Hindi | Original Album | MM Kreem |

| 16 December | Karthik Raja | ||

| Mukhbiir | Karthik Raja | ||

| Vellu Nayakan | Tamil | Nayagan | Illayaraja |

Notes:

- For those interested in dubbing and translation, look up the name Irina Nistor, the woman whose voice brought Hollywood to Communist Romania.