This is a good time to mention that Susheela Raman has a new album that came out last year, called Ghost Gamelan.

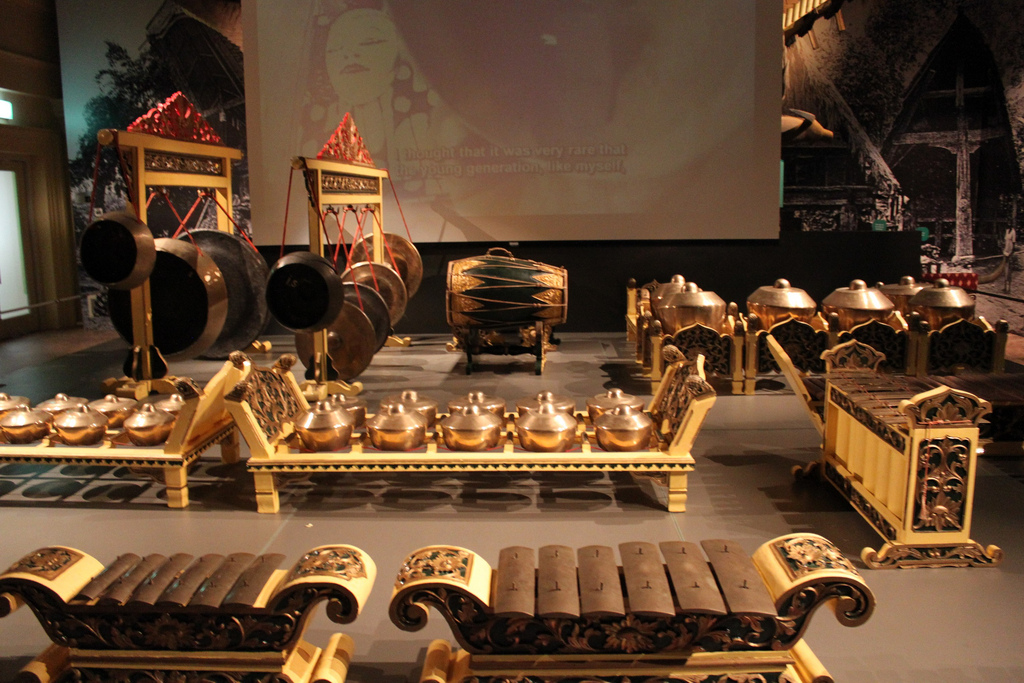

In case you didn’t know, Gamelan is a form of traditional music from Indonesia, primarily the islands of Bali and Java. The music is percussive, and its origins lie in Javanese mythology, from the story of a king who summoned the gods by playing on three gongs. So while gamelan incorporates a variety of musical instruments, the majority of the world identifies it via the distinctive sound of the metallic and bamboo gongs, xylophones, and cymbals that are used in the ensemble.

The first time I heard the sound of gamelan was, even though I did not know it then, the soundtrack of Akira. The layered, propulsive beats that underscored the violent motorcycle chase sequence in the opening moments of the film was all bamboo and metal gongs. The sound captures the frantic energy onscreen with perfection, and still manages to pump me up every time the beats kick in. For a movie that released in 1988, the music does not sound the least bit dated. (Contrast this with another sci-fi anime epic that released in the same time period -– I adore Joe Hisaishi, but the Nausicaa OST screams its time-period from the first synth-note)

Raman’s album, in contrast to Akira, fluctuates between percussion-heavy pieces (‘Tanpa Nama’) and slow, meditative pieces (‘Beautiful Moon’, ‘Spoons’) that accentuate the moodiness the musical form is capable of. Sometimes, her lyrics and the main melody dance around the traditional music elegantly, yin and yang (‘Ghost Child’); in others, voice and gong echo in unison. ‘Annabel’ is probably the only track that is old-school Susheela, and is a wonder unto itself. Oh, and the last song ‘Rose’ features lyrics by William Blake. While I don’t like quoting promotional material from album releases, the official text describes the music far better than I can:

https://bit.ly/2PpKqxa

Javanese music evokes the invisible; ancestral presences, old religions, volcanic rumblings, and court intrigues. A sensuality of appearances, decorum, ritual and procession runs to trance and possession. Meanwhile, Raman’s songs here are meditations on change, transformation and mortality. Lyrics reflect on uncertainties cast by memory, desire and the ephemeral. In this album, tonality and rhythm are questioned and de-centred, just as much as they are asserted. Some records achieve a fixed quality but this record is very ‘alive’, or volatile, both in the performances but also in the way it shifts as you hear it. The vitality of the interactions, of the musical cultures misbehaving with each other, result in a sound more ‘unearthly’ than ‘world’.

A major part of the album depends on the skills of Raman’s collaborator, Javanese musician Godrang Gunarto and his ensemble. You can see them live here (apparently, they have been touring together since 2017) , wait for 3:42.

One of my favorite experiences with gamelan was a Hammer museum exhibit called The Gamelatron, from two years ago. This was an open-air installation featuring a five-piece kinetic sculpture that used robotics, metal gongs, and timers to play gamelan-inspired music. Viewers were encouraged to lounge around in seating areas and soak in the harmonies that played throughout the day. It was a blissful hour, and I remember coming out of the exhibit feeling rejuvenated.

I loved revisiting the music of Susheela Raman. It’s been 13-odd years since I heard Love Trap for the first time (and forged a life-long friendship in part because of a mutual love for her album). I hadn’t listened to her in years; a Whatsapp message earlier this year brought her again into my periphery, and this apparently is what I missed since 2011:

- a 2011 album called Vel, which I never listened to

- a cover of a Naushad song called ‘Mohabbat Ki Jhoothi Kahaani’ for a 2013 movie called Kajarya (which strays into familiar territory as ‘Yeh Mera Deewanapan Hai’ from Love Trap)

- a strange 2014 album called Queen Between, which features Raman collaborating with neither available on Spotify in the US, nor via any online music stores. Amazon has a (used) CD for sale, so it looks like this was never released in the US. So here we are, in 2019, unable to listen to an album with a few keystrokes and minimal latency. What is this world coming to?

At this point, our intrepid music explorer remembers this little-known site called Youtube, and he blushes at his tirade against digital tyranny. “I recant”, he exclaims, as his senses are filled with chocolate and chiffon, marshmallow and clouds. Behold, unbelievers, the joys of ‘Sharabi’, by Susheela Raman and Rizwan Muazzam.