I think Man of Steel was a better movie than most of what Marvel has produced so far, including Avengers.

Earth-shattering spoilers follow, one that will brutalize your first viewing of Man of Steel and leave you a broken human being. Proceed at your peril.

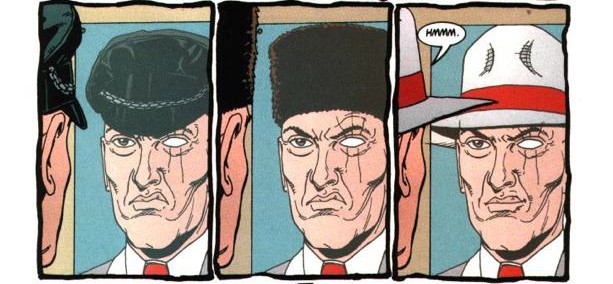

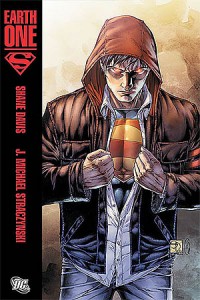

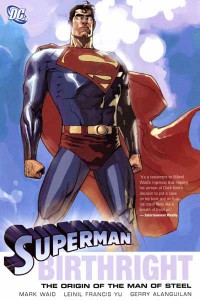

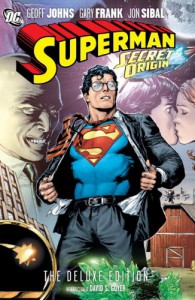

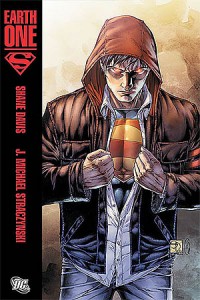

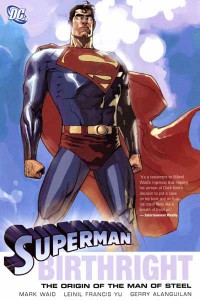

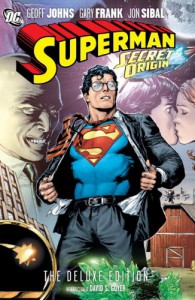

The Dark Knight trilogy had it good – there were already iconic Batman stories in DC canon that could be strip-mined for imagery and a coherent feel. The entire Marvel-verse movies borrow heavily from the character portrayals and arcs in Millar/Hitch’s Ultimates. Superman? There really is no definitive Superman origin story. Mark Waid wrote one. It was pretty darn good, but not many people have read it and it’s not even considered canon. Geoff Johns wrote another, and it’s so weighed down by 60+ years of continuity horse-shit that you need to go take a shower half-way through it just to get rid of the fan-boy stench. You know, all that sweat from trying to understand who the fuck the Legion of Superheroes are and why they are relevant to Superman’s life. There is an “original graphic novel” called Superman: Earth One that you can read if you are feeling particularly masochistic someday. It’s written by J Michael Straczynsky and it has emo Clark Kent in a hoody. Yup, you read that right. All-Star Superman? Gorgeous, but ultimately a psychedelic tribute to the zany Mort Weisinger era of the fifties. Whatever Happened to Man of Tomorrow, Kingdom Come, Red Son, Death of Superman – good luck reading them as a newcomer to comics.

Super: Earth One. Super-crap.

Superman: Birthright. Nice, but hollow and overly respectful.

Superman: Secret Origin. Or how Fanboys Fellate the Movies and Comics of Their Childhood

So it’s no surprise that the template for Man of Steel – the pacing, the beats of the story, the way the events in Clark Kent’s adulthood intersect with key events in his past – seems entirely based on the innards of the Movie That Worked, David Goyer’s script to Batman Begins.

(Someone more qualified should also talk about the role of the father figure in Goyer’s scripts. Both the movies reveal a great deal of influence their daddies had on the respective superheroes. Martha Wayne had zero lines, and Lara Lor-Van has a few, but not substantial. Yes, I know Diane Lane’s character contradicts my observation, but whoever lets facts get in the way of criticism?)

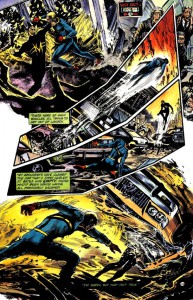

People talking about the 9/11 hangover in the movie, please stop. All falling skyscrapers need not allude to that particular day in American history. If in doubt, please refer to scenes in Miracleman #15, which is still held up as the definitive destruction sequence in comics. While a generation of moviegoers fondly reminiscence over the Donner movies – yes, he made us believe that a man can fly – but a man who is faster than a speeding bullet fights another of his kind, people become chicken-feed and buildings are toilet paper. The closest American cinema got to this was in the final showdown in Matrix: Revolutions, and that supposedly occurred in the virtual world, with non-human onlookers bearing witness. This? This was cinematic destruction amped up beyond comprehension, where we see technology trying to show us what happens when titans clash. (And Morpheus and Locke appear in it too, though not in the same frame. Matrix fist-bump, y’all!)

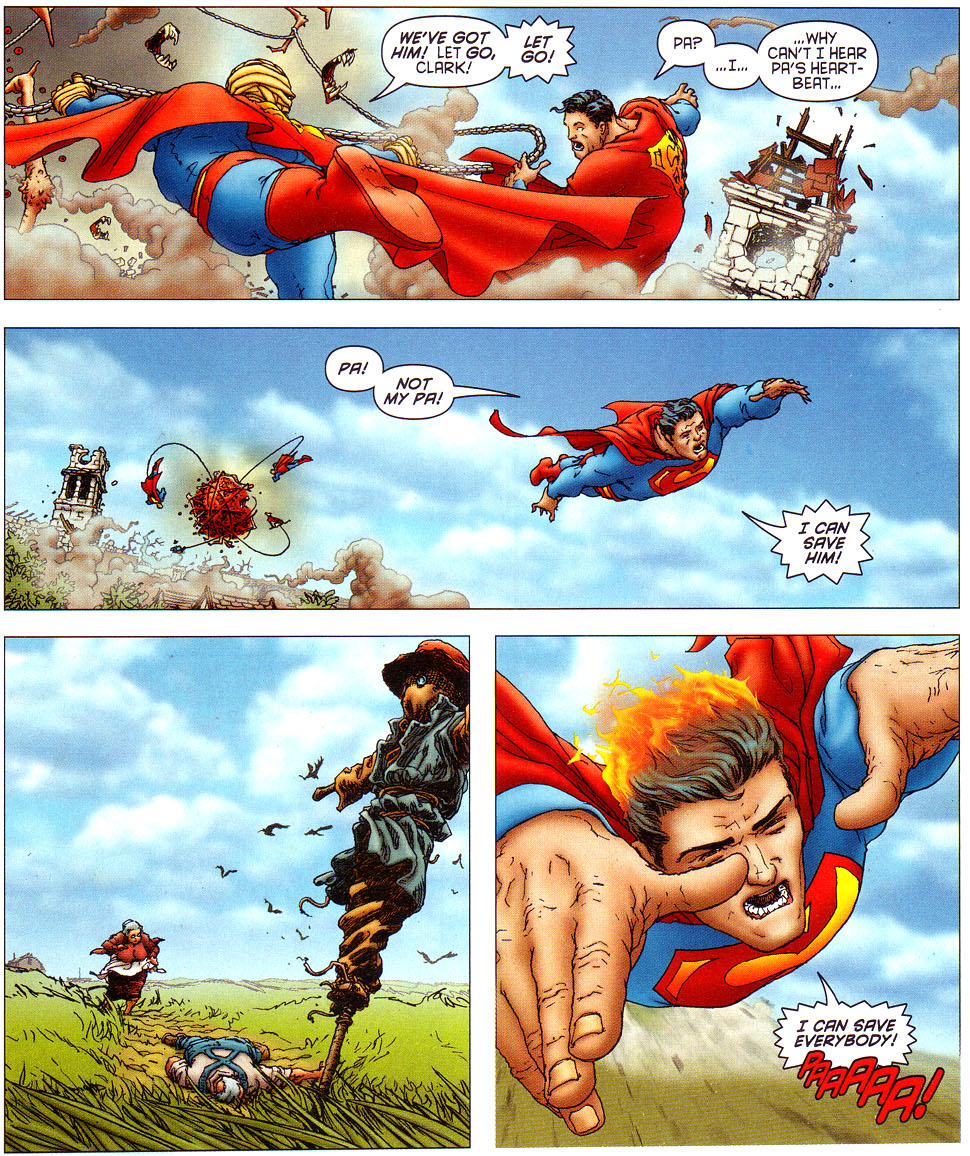

I have a low opinion of Zach Snyder. Most of it stemmed from the fact that the man’s only claim to being a “visionary” was slow-motion fight sequences where you hear bones breaking. Dawn of the Dead was meh, and his adaptations of 300 and Watchmen (the latter of which, in all fairness, I could not sit through beyond 20 minutes) were so slavish to the source material that there was no sign of any directorial authority in either. Unless you count color-toning films as auteur-vision. Whatevs. MoS however revealed a very sentimental side of Snyder – he actually paid attention to the quiet moments. Clark falling to the depths of the ocean, Lara looking at her planet’s final moments; “focus on my voice”; “you can save them all”. Beautiful.

Don’t expect Snyder’s osteomania to let up in this movie – the first few minutes have Russell Crowe inflicting major vertebral violence on his co-planetary compatriots. (On an aside, what the fuck is up with these highly advanced planets? Aren’t there nations? Factions? Different skin colors? Opposition parties that do not resort to violence? Or is all pulp science fiction proof that democracy as a concept has to be cast aside for a civilization to flourish? Whoa, deep.) The slow-mo sequences, however are hasta la vista, baby. The action sequences involving the Kryptonians are furious blurs – all that’s missing are speed-lines. However, time slowed down whenever Antja Traue was around. For me, at least.

Man of Steel‘s worst offence is not its own, however. It is a byproduct of this current decade’s technological excesses applied to cinema. The , in particular the greyish-blue aesthetic that taints everything you see on screen: costumes, cultural paraphernalia, technology. Everything from spaceships to personal assistants are monochrome, and the skies turn ominously dark at all major events. It is like we live – or rather, our cinematic imagination lives – in a universe that came about after a to-the-death grudge-match between the design aesthetics of HR Giger and Moebius, and Giger’s palette overpowered the sunny outlook that Moebius’s works had. That, or someone took the word “cinereal” a little too literally. Once again, this is not something I aim at Man of Steel in particular, look at every single summer blockbuster out there, and that same mournful look permeates throughout. The curse of this decade, I say, and I will be glad when the winds of change sweep over animation render-farms across the world.

Those who say that Superman does not kill: please, this is not a comic-book. There is no comics code authority that shelters the children of the world from fictional violence. There is no editorial panel that wants a rogues’ gallery that can be rotated every few months or years. Drop it, you guys. You cannot lay boundaries on a fictional character, especially not after Sherlock Holmes has been seen using a cellphone.

Yes, I did not like most of the Marvel movies. That is because they are predictable and they have no consistent tone. The Avengers was fun because it was the first time we saw a team movie, plus Joss Whedon’s lines. As a story? You need to talk to my French friend. Her name is Cliché and she has a pet cat called Whimper.