(A modified version of this was originally published in Rolling Stone India, November 2008.)

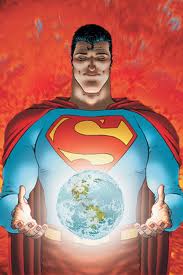

All Star Superman

It ‘s interesting (and a little surprising) to note that flagship characters like Superman or Mickey Mouse, both of whom have been around for the greater part of a century, have very little in terms of memorable stories starring them. More so in case of Superman, whose universal recognizance is equated with one-dimensionality, whose corporate image is so strong that just last month, a Superman comic whose cover showed Clark Kent sharing a beer with his father was pulped and reprinted, the label on the bottle on the new cover saying “soda pop” instead. There’s also the problem of the storytelling engine associated with the character – Spider-man has a low bank account and woman problems, just like the rest of us; Batman is dark and psychologically complex enough to appeal to the insecurities of the valium generation, but Superman – a god-like being whose sympathies lie with the human race, whose limitless powers are channeled for the betterment of mankind – pisses off our cynical selves. We just cannot wrap our minds around the concept. Superman is boring. Superman is a square.

Grant Morrison does not agree. A Scottish writer known for his 90s’ revamp of half-forgotten Silver Age DC characters like Animal Man and Doom Patrol, Morrison took up the reins of coming up with a distilled version of the Superman character. Morrison’s vision of Superman is one that is unencumbered by all these years of continuity baggage. He expects the reader to be onboard from the get-go – succinctly displayed by his recounting of the familiar origin in four phrases, on four panels, on one page. Morrison’s Superman was in no way removed from the iconic character we know. Nothing is different, yet everything is new. These twelve issues of All-Star Superman are, without doubt, the greatest Superman story ever written.

The first thing that hits you when you read All-Star Superman (and I recommend you do so in a single sitting, for optimal effect) is the chutzpah of the writer. The overall arc, made up of single and double-issue stories, revolves around the idea of Superman’s own mortality. In the first few pages, Superman discovers that he is dying, because of a trap laid down by his arch enemy Lex Luthor. Before his death, he has to conclude his earthly affairs and, according to a messenger from the future, must accomplish twelve feats that will save multiple universes. As the story progresses, we travel galaxies, dimensions and time-lines with the Man of Steel, as he battles his own fate and finally surrenders to it. The last few issues proceed at a break-neck pace (and yet, with moments of quiet calm) to an ending that reflects grief, awe and hope.

In an industry primarily known for recycling themes, Morrison spews out fresh, hallucinatory ideas in every other page. Throw-away lines speak of voluminous histories – characters like the Subterranausauri, led by Dino-Czar Tyrannko, the Ultra-Sphinx, Zibarro, Luthor’s assistant Nasthalthia ( “call me Nasty!”), super-scientist Leo Quintum could stand on their own and provide fodder for years and years of super-stories. While these new additions to the Super-stable, along with the familiar members of the cast – Jimmy Olsen and his signal watch, Lois Lane, Perry White, the Kents, the Phantom Zone, the Bottle City of Kandor, Krypto the Super Dog – have integral parts to play in Morrison’s epic, the storyline is still about Superman. The coolest thing about the writer is the way he gets the Man of Steel like no one else before him has. (Consider a line like this – “As she spoke, I watched 35000 dead skin cells scattering like confetti…like promises…like the dust of dead stars”.)

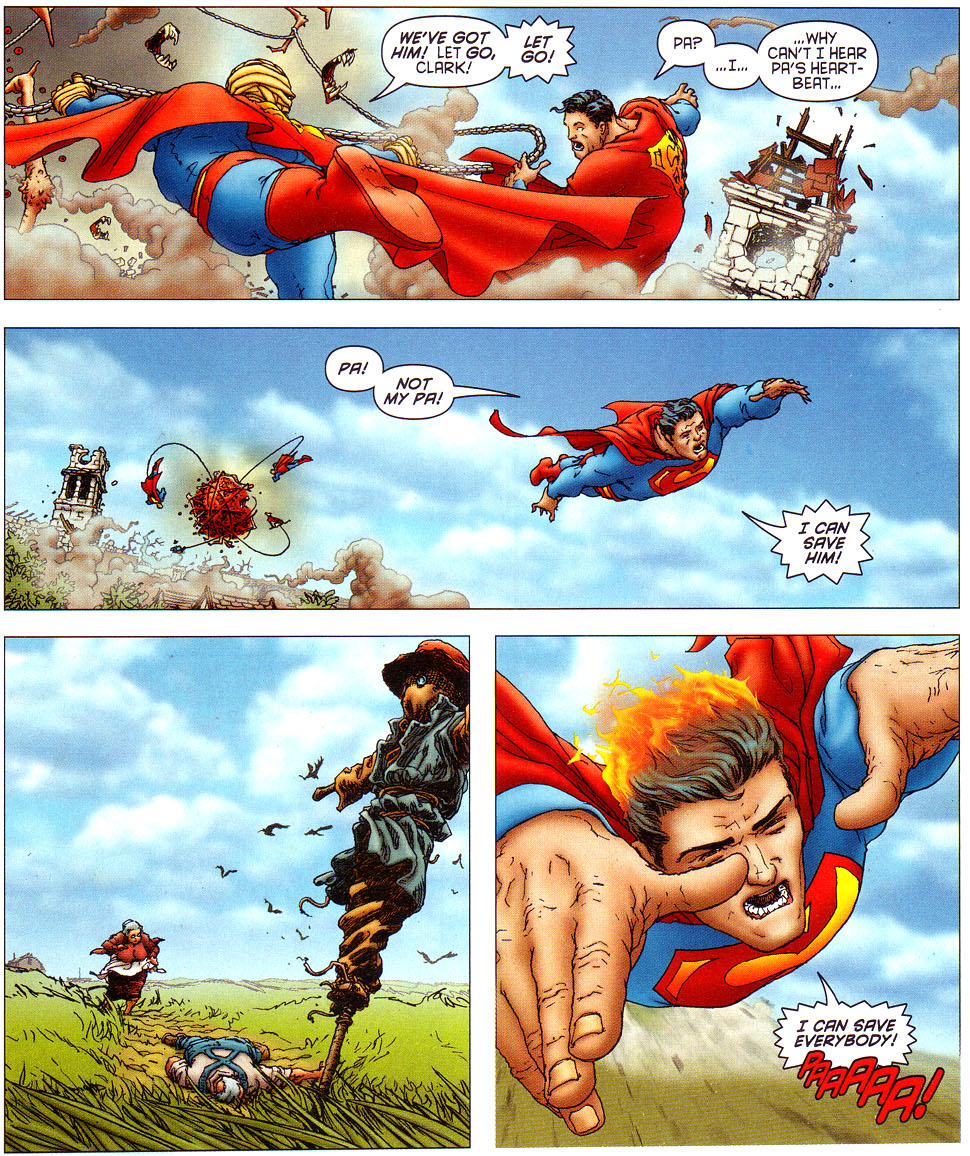

It is to artist Frank Quitely’s credit that he takes all of Morrison’s ideas and brings them to life. Quitely, Morrison’s long-time collaborator weaves the writer’s threads into a shining tapestry of lines and colors; his Superman is lazy-eyed and self-assured, godly and yet human. His traditional panels – a far cry from his anti-geometric experiments evident in WE3 and Flex Mentallo, gives the story a quiet dignity, just as his full-page splashes punctuate its most unforgettable moments. A teenage Superman flying to save his father is just as hard to forget as the image of the Man of Steel kissing Lois on the moon. Jamie Grant’s colours over Quitely’s unique pencils permeate the book with a distinct glow, one that makes it stand out from the profusion of muddily-colored superhero books on sale nowadays.

A kiss on the moon

Not that the book does not have its share of negatives. For as good a writer Morrison is, he is also too clever sometimes, deliberately opting for confusing panel transitions and obfuscated storytelling to bombard us with his postmodern interpretation of the Bizarro world – where we encounter Zibarro, the Bizarro Bizarro. (2013 update: I have warmed to the Bizarro storyline since I read it last) I also have a problem with portraying Lex Luthor as a self-important, deluded buffoon; in seeking to inject his stories with the flaky trippiness of stories from the 50s, Morrison undoes the depth the character has been imbued with over the years. But that’s just my inner nerd whinery, never mind.

There have been some good Superman stories over the years, of course. But for one or two meaningful stories, the monthly comics are rife with hackery, wherein writers tried to come up with gimmicks to appeal to fans – Superman died, was resurrected, got a new hairstyle, got married, got a new costume with electrical powers, had multiple reboots of his origin. Of course, none of it really stuck. All-Star Superman, on the other hand, is everything the monthly Superman series is not, and should have been. It is a moving story of a hero that has withstood half a century of cultural ripples. A hero who is not one of us, but one we can aspire to be.