(Originally published in the July 2009 issue of Rolling Stone India)

Adrian Tomine (pronounced Toh-mee-nay, not Toe-mine, as many people think) wears a lot of hats. Metaphorically speaking, of course. His current assignments include illustration gigs with the New Yorker and Esquire, designing indie DVD covers, and editing/overseeing arthouse manga for the publishing house Drawn and Quarterly. But Tomine is not known for these interesting career forks as much as he is revered for the series of mini-comics, called Optic Nerve, which he began at the age of 17.

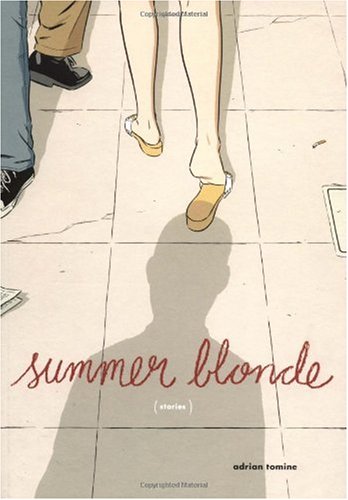

Summer Blonde, the third collection of the creator’s Optic Nerve series, has four stories. ‘Alter Ego’ is about Martin Courtney, a moderately successful writer experiencing writer’s block under the pressure of meeting and surpassing his debut effort. As he puts it, “They say everyone has one great book in them. Maybe I had a mediocre one and that’s it.” Things take a strange turn when he gets a postcard from an old schoolmate he had a crush on, and begins dating her younger sister, who’s still in high school. ‘Summer Blonde,’ the second story has twenty-something Neil, single, obsessed with a girl who sits behind the counter at a greeting card shop who he buys a card from every other day but cannot muster up the courage to ask her out. When she begins dating his neighbor Carlo, a man who knows his way around women, Neil becomes an unwitting stalker of the girl he cares for. Hillary Chan, the protagonist of ‘Hawaiian Getaway’ calls random strangers passing by the phonebooth next to her apartment, desperate to strike up a conversation with anyone at all, after being fired from her job and abandoned by her roommate. ‘Bomb Scare’ is set in a high school, where a boy – a member of the geek clique in the class – strikes up a friendship with popular Cammie, who has just had a traumatic experience at a party.

All these synopses make it sound like the stories go somewhere, but they don’t – think of them more as stray reels of unfinished films. Every story ends, rather, is interrupted, at a point where, in a “normal” plot, there would be a major emotional turning point for the characters involved. Be warned, if you seek happy endings in your stories, or some form of closure for the protagonists, you won’t get that from Tomine’s work. Neil, the protagonist of the second story, meets the girl inadvertently in a crowded subway train, and as they’re pressed against each other, he stumbles to find the right words. “I am sure…you really hate me,” his voice trails off. Pause. “Yeah, but no more than anyone else,” she replies, still looking away from him. End of story.

A striking aspect of Tomine’s comics is the hallucinatory nature of what he writes and draws – the kind that leaves you slightly off-kilter once you’re done imbibing them. It’s the kind of buzz you get from a Michel Gondry film, or a Bjork video, or a Weezer song. All in all, these are more experiences than actual stories. His characters are real, flawed, everyday individuals, riddled with insecurities, bearing the weight of misguided intentions, the kind that one wouldn’t notice in a crowd. They are also fucking creepy, just so you know.

Part of what keeps you engaged throughout are the interesting and varied storytelling techniques. Flashback panels, narrative captions and thought balloons, often avoided by modern comic writers, are employed by Tomine to evoke a unique emotional effect. Observe the way he manipulates silence to optimum effect. Silent panels take the story forward, let us into the mental turmoil of the characters, mark the passing of time, even freeze a few moments into an eternity. This is a comic book auteur who knows the tricks of the trade, and uses them to splendid effect.

In many ways, Tomine’s work is a natural progression of the underground comix movement of the seventies, started by the likes of Robert Crumb, nurtured by stalwarts like Pulitzer winner Art Spiegelman and Charles Burns, and given shape and form in the last part of the century by talents such as Dan Clowes, the Hernandez brothers, and Chris Ware. The creator has openly acknowledged the influence of Clowes and the Hernandez brothers in his work –the clean-lined style of his character drawings, in particular, and the deceptively simple backgrounds owe a lot to Clowes’ Ghost World and David Boring. Also, among the hardest things to do when you’re drawing comics is to create people whose faces, body structure and mannerisms do not meld into one or two oft-used templates with hair color or a costume being the only distinguishable way to identify a character. Tomine’s artwork leaves no doubt in your mind about his complete proficiency in this area – every single character is singularly drawn, each just as ugly or plain or pretty as the story demands.

Among the allegations made by his detractors is his inability to stray from his comfort zone, making all his work suspiciously similar. But there is no taking away the power in Tomine’s work to echo the human condition. The stories are about Americans, yet they resonate with every individual in any society who has ever felt alienated, lonely or loveless. Isn’t that what art is all about?