I had nothing much to do today morning, decided to come to the office and check out some bookmarked sites, and one of them happened to be The Comics Journal. A quick checkout of the column archives took me to this article, and I was struck by these lines there….especially the words I have highlighted in bold.

The first truly great comics book of the new millennium was published in early 2001, a collection of a weekly newspaper strip that was launched over a decade ago. Odds are, you’ve never heard of it: Peter Blegvad’s The Book of Leviathan. I’m convinced that there are now two types of people in the world: people who agree with me on the above, and people who haven’t read it yet. In a Hit List review in TCJ #234, the esteemed Ng Suat Tong wrote, “A rare instance in which the label ‘essential’ is not misplaced, Leviathan is one of the great strips of the last decade.”

It’s disturbing and disappointing that work of this caliber has gone unnoticed in the United States for so long. Brit-by-way-of-New-York Blegvad’s strip Leviathan, published in London’s The Independent on Sunday, was launched in 1991. Had his strip been syndicated to just a few alternative weeklies on the other side of the pond, I have little doubt that Blegvad would have already been inducted into the contemporary pantheon (pun possibly intended) of Ware, Katchor, Clowes, Spiegelman, et al.

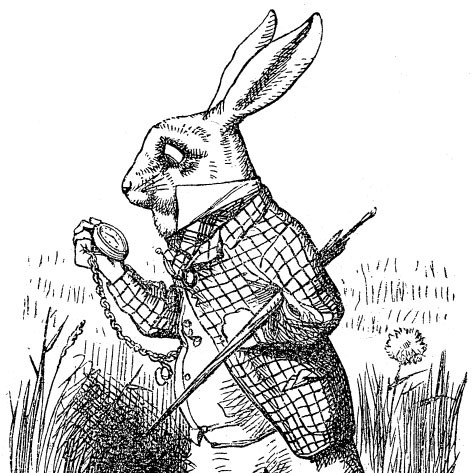

This paradigm-shift-inducing piece of Art stars the faceless baby Levi(athan), the pet cat Cat and battered stuffed-animal Bunny. Levi’s skewed view of life is the focus of the strip; his misunderstandings and, occasionally, outright rejections of adult life and logic — what we assume to be reality — are the base that the strip is built on. Levi & co. travel to other dimensions and spelunk the hidden mysteries of their home.

What makes this book great is that it allows life’s facade to slip just enough to show the reader how unfathomably complex the machinery of our shared existence is; it’s a playful jab in the ribs that reminds us that, for all our talk, we will never fully understand our surroundings in our lifetimes. Blegvad, through Leviathan, shows us that there are other valid perceptions of reality; he cracks wise about the very nature of human understanding — have we truly built our understanding on the right foundation (our parents’) or did we build on the closest one to us, just as our parents did before us? – and it still works as someone just cracking wise. No mean feat.

Rafi Zabor notes in his introduction that The Book is but the tip of Blegvad’s comics iceberg; it contains 150-odd Leviathan strips, meaning that there are two more Volumes worth of, according to Zabor, darker and less funny-haha material waiting to be collected and published. The Book mostly focuses on the humor continuities, but its first chapter is a chilling story of Levi searching for his dead parents. The arc grabs you right at the spine, reminding you of the overwhelming fear of abandonment you had at that age, when your toys and family were literally the only things you had. The story also works as an impressionistic picture of the arbitrary, ironclad rules (that must be followed, Or Else) that children believe they live under. It demonstrates Blegvad’s skill for tapping into early fears and thoughts in childhood, and making them palpable to adults who thought they had long since forgotten them. If there are six more years of comics this affecting, then bring them on.

Blegvad uses an astounding range of styles to illustrate his and his characters’ thoughts on things like philosophy, science and poetry, usually working in a few ridiculous textual and/or graphic puns for the ride. Leviathan is, technically, a full-color strip, though the artist seems to use color as needed, most strips being B&W save Levi’s sea-green sleepers and the pink Bunny. Other strips are eye-singeing explosions of color. A strip that looks like it was engraved centuries ago could sit next to one that appears to have been done by computer last year and would they still work as a continuity. Blegvad even shifts into a non-representational style to draw impressions of sounds for a strip where Levi is awakening to the sounds of his neighborhood. Appropriately, the artist’s visual style is as elastic as his protagonist’s sense of reality.

Both being fanciful child-and-cat strips, there is an obvious comparison to make of Leviathan to Calvin & Hobbes. But as great a cartoonist as Bill Watterson is, he’s no Peter Blegvad, and Calvin and Hobbes are skilled vaudevillians doing cutesy shtick when compared to Leviathan’s Byzantine wonders. Even Blegvad’s throwaway jokes show a level of thought and insight rarely seen in any medium, much less comics. Leviathan is closer to Hobbes the philosopher than Hobbes the stuffed tiger.

I guess therein lies the difference between a syndicated strip and undiscovered genius. I went and did a recursive “wget” on the Leviathan archives at http://www.leviathan.co.uk. There weren’t too many of them, and I read the first one, entitled “Orpheus”. It’s really, truly good!! How brilliant it is, well, I don’t think I can really go into details, because this is just one story that I read. Yes, the inherent humour is a little more sinister. I don’t think people would appreciate getting Levi strips every morning in their mailbox. :-)

At last, some one dares to point out the mediocrity and I-HAVE-to-produce-a-cartoon-a-day mentatlity behind Calvin and Hobbes.

C&H is cute, and at times, when you are in a good mood, you find it funny. The skilled vaudevillians etc etc statement hit home, really. But I have to disagree with you on “mediocrity”. “Overhyped” would be a better word.

I hope you went and checked out the Leviathan strips.