This!

The Complete Don Martin slipcase edition.

And this.

Lagaan 3-DVD box set

MUHUAHAHAHAHAHA!

This comment thread, where gamera_spinning explains something of the Continuity Clusterfuck that DC Comics is undergoing right now makes me believe that the venerable comic company is trying very hard to break my mind. But I won’t give in, I won’t. I promise to stay abreast of all, I repeat, ALL braindead changes that occur in the DC Universe.

P.S Out of all the facts retold in the comment thread,the Mary Marvel storyline was the only one that escaped my general DC consciousness.

I read Adam Warren’s Empowered volumes 1 and 2 this Saturday. Must rank as one of the most seamless merging of the superhero genre and (what is commonly referred to as ) manga style of drawing. Adam Warren is one of the earliest creators of Original English-Language Manga ( OEM ), his work on The Dirty Pair hitting bookstores a long long time before manga attained the level of popularity we see today. Empowered is a kick-ass piece of work, combining absurdist humour with superhero cliches, taking the damsel-in-distress gag to ludicrous heights. The series is chockful of quirky characters – our disaster-prone heroine, her boyfriend, a thug named Thugboy – with a former career of filching equipment of super-villains by pretending to be a brainless minion, her best friend Ninjette, a heavy-drinking, ass-kicking ninja princess, The Caged Demonwolf, a Lovecraftian monster who has been trapped inside an energy-draining belt and now spends his free time watching TV from Empowered’s living room, the Super-homeys, the bunch of upright superheroes with whom Empowered hangs out and her arch-nemesis, Sistah Spooky, who resents blonde women. All in all, a romp of a series – I love the fact that Warren is not just having fun, but is also introducing subplots that make me await the next volumes impatiently. The artwork is all black-and-white, being shot entirely from Warren’s pencils ( though I detect a marker or two, in the blacks ).

And also reading the first two trades of Brubaker-Lark’s Daredevil run, The Devil, Inside and Out volumes 1 and 2. I cannot stop drooling over Lark’s artwork; just when I thought Maleev had brought in a new scratchy feel to Daredevil’s adventures, Lark takes that style, makes it his own and does wonders with it. Ed Brubaker – someone stop that guy! His writing is so perfect for the street-level grittiness that Daredevil needs. The added bonus is that he does not indulge in conversation-masturbation, the way Bendis did in his series, when all you had were talking heads that indulged in random, forced conversation just because the writer felt like it. The fag end of the Bendis-Maleev run, especially Decalogue and The Murdock Papersare tough to read just because they are so BORING. Here, though, the action and the quiet moments happen in perfectly-timed beats, and all I can say is, dang, I want to see where this series goes.

Also read this Dr Strange mini called The Oath, by Brian K Vaughan and Marcos Martin. I am not a big Dr Strange fan, and while the series goes very deep into the mythos of the good doctor, Vaughan’s writing made it fairly clear for me to figure out what was going on. I dig Martin’s art, from the Batgirl: Year One series, it’s very Mazzuchelli-influenced, or so it seems.

And THAT is the reason why there isn’t any new Lone Wolf and Cub post yet.

Cliched as it may sound, Om Shanti Om redefines the term “masala film” for our generation. Ok, so it’s a love story. It’s a reincarnation theme. It’s also a spoof of Bollywood in the seventies and of the present-day star-son/guest-appearance syndrome. At parts, it becomes a horror movie, or at least tries to. It makes over-acting an integral part of the script. Yes, and lest you say “there was no script”, I beg to disagree. Loved every minute of it, and bunked office on Tuesday to go check out the IMAX version. Current count: 3.

The film is a complete exercise in over-the-top chutzpah – the icing on the cake would have been if FK had gotten Karan Johar to speak to the camera during the award ceremony, and say – “Om Kapoor and I are just friends.” The self-inflated star cameos were BRILLIANT – it was almost like the actors took the personalities one would associate with them and turned them all the way up to 11. Part of this unabashed attitude is reflected in the song lyrics – I hardly ever notice words to songs unless they are Gulzar’s lines tuned by Vishal Bharadwaj – but rhyming “pichhle mahiney ki chhabbisko” with “dil mein mere hai dard-e-disco” is hardcore, man. Respect, Javed Akhtar. And the composer duo Vishal-Shekhar, in particular Vishal Dadlani manages to floor me everytime – he’s the lead singer of Pentagram the band, who blew me away the day I heard him sing Bjork’s ‘Army of Me’ on stage. He is at home composing a cheesy Bollywood number like ‘Dil Dooba’ ( Khakee), goes on to sing the catchy ‘Kiss of Love’ in Jhoom Baraabar Jhoom and now, apart from composing the songs in OSO, writes the lyrics to ‘Ajab Si’ – man, the line “dil ko banaade jo patang, saansey teri woh hawaaye hai” just kills me. Also, the man makes a guest appearance as the microphone-twirling director of Mohabbat-man, bwahahahaha.

And the references. Right from the seventies billboards of Schweppes and Exide batteries – to the small details (a poster of ‘Baali Umar Ko Salaam’ hangs on the wall, the debut film of our heroince Shantipriya, referenced in a throwaway line somewhere in the first half). Manoj Kumar’s driving license, Subhash Ghai getting into the directorial groove, Mohabbat-man, the making of Apahij Pyaar, Tiger fights – I could go on, you know that? This kind of self-referential, in-joke-laden storytelling gets to you most of the times, but not in Om Shanti Om. This is the kind of film that begs you to grab a bucket of popcorn, sink into a chair and laugh along with it. And then when the film is over, you need to go back and figure out how many of the jokes you missed the first time around. Inspired lunacy does that to you.

I also saw Mahesh Bhatt’s Dhokha this week. Nice plot, about a Muslim police officer whose life falls apart when he learns his wife is a suicide bomber. In true-blue Vishesh Films’ fashion, the overblown script-writing and the non-existent acting proceeds to drive the plot towards a predictable conclusion. Pathetic execution.

And I bought the newly-released two-disc edition of Chak De India on Friday, and then watched the film a couple of times on Sunday. The deleted scenes, in this case, are scenes which have been editted out from the final cut, with a lot of subplots and incidents missing. One of the hockey girls, in particular, gets the short end of the stick, with her story being a prominent subplot that gets excised. And my DVD player refused to go beyond the interval, which I think was because of the layer transition in the DVD. I had to finish it on my PC instead.

Other things of note: Downloaded Samurai Wolf and Samurai Wolf 2. And am FINALLY getting the Female Prisoner Scorpion boxed set, woo hoo!!

And also, for the first time ever, ALL my books are back with me, from various parts of the world.

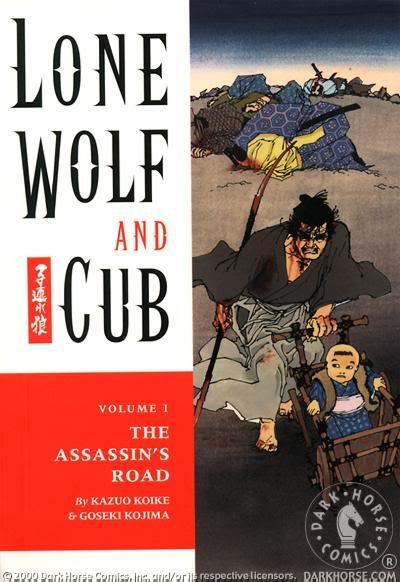

I refer to the first four volumes of LW&C as the Meifumado arc, which consists of a series of adventures that do not follow a timeline per se, jumping about the place in terms of timeline and after-effects of one episode following the other. There is an internal continuity to some of the stories, in particular those that deal with the beginning of Ogami Itto and Daigoro’s journey. The origin story, so to speak.

Meifumado is the Buddhist term for hell, a place inhabited by demons of Japanese myth. (This is the definition given by Koike in the book, and I am not sufficiently well-versed in Buddhist Theology to determine the deeper meaning of the term.) It is the path chosen by Ogami Itto following a tragic event in his life. Once a man with twenty-seven years of dedicated service to the Shogun behind him, it was a culmination of circumstances – part of which was instigated by political rivals, that forced Itto to abandon the way of Bushido and travel the path of hell, the life of an assassin. At first glance, there isn’t much difference between Itto’s previous incarnation and this – both involved bloodshed, corpses and a hardened heart. But while the post of the shogun’s executioner required a blind allegiance to duty, the road to Meifumado was akin to that of an outlaw, free of society’s rules and moires, with the lives taken paid for with the sum of five hundred ryos.

How do Koike and Kojima inject life into a series that, at surface value, is the life of an assassin? It’s surprising to see the storytelling techniques at display here. The assumption the reader needs to make, while beginning a story in the early Lone Wolf and Cub stories is the invulnerability of the duo. There are more than 7000 pages to go before the journey concludes, and its fairly obvious that no major harm would come to the eponymous protagonists in the initial stories.

It would also be right to emphasise that these stories are not necessarily about Lone Wolf and Cub, they sometimes involve these characters as a plot resolution of some form. Some of them are a study in the twisted nature of vengeance – like the fourteenth story – Winter Flower ( volume 2). The story begins as a police procedural in an unnamed town, where the inspector of the province investigates the double-murder of a couple and a prostitute’s suicide, both seemingly unrelated, but as the story goes by, we see the connections unfold through the eyes of the investigating officer. How the presence of a mysterious ronin accompanied by a baby in the vicinity tie in to the deaths are explained at the very end, when the officer looks at a winter flower given to him by the ronin – the same flower that was found at the murder-site, and understands for himself as the strands of the story come together. Some stories involve the accidental involvement of Ogami Itto and his son, the story The Virgin and the Whore being a particular example. A young girl, sold into prostitution, tries to escape her fate by killing the man about to escort her to the brothel. While running away from the yakuza gang which has bought her, she takes shelter in an inn, incidentally inside the same room that was occupied by Ogami Itto and his son. When the gang-leader, a shrewd lady, humbly requests the ronin for the girl he is sheltering, an interesting chain of events occur. Was it just coincidence that the assassin was at the inn or was all of it an elaborate ruse to carry through a hit? Don’t worry, the ending comes as a surprise, regardless of what you might assume at this point.

Political intrigues of the period take precedence in most of the assassination plots that involve Ogami Itto. In the story Close Quarters ( Volume 3) a clan requires him to dispose of dissidents who oppose the cutting down of a forest – the clan leaders want to reduce their trade debt to merchants by supplying Edo with wood at lower rates, while the rebels claim that destroying the forest would cause their towns to be flooded during rainfall. Itto is contracted to kill the dissedents without the forest being destroyed, because the dissidents have lodged themselves at strategic points, threatening to burn the trees before letting their leaders chop them down in the name of commerce. There is the peculiar request of the father in The Bell Warden, an official entrusted with the task of maintaining the official Town Bells in Edo, who wants his three sons to duel with the Lone Wolf in a bid to select the worthiest of them to carry on the family occupation. The Coming of the Cold makes Ogami Itto impersonate a law official to infiltrate a clan castle and assassinate the clan elder – the catch being that the contract is placed by the faithful retainers of the clan who feel the leader’s actions would cause them to lose face.

“To Lose Face” – something that is one of the most important aspects of feudal Japanese society, where honour and personal loyalty were considered greater than one’s life, if one were a samurai. Lone Wolf and Cub plays on this theme a lot, revelling in this singular Japanese trait and at the same time showing it for the vainglorious relic it was. In all the examples mentioned above, “face” plays a major role in determining the course of action of the people concerned, even among those not from samurai society. One of the principles we twenty-first century beings might find outdated ( not to mention bizarre) is the concept of regaining one’s honour through killing oneself, but it was a way of life then, and Lone Wolf and Cub also becomes an examination of bushido, from that standpoint. It’s interesting to see how the themes of honour and vengeance are interlocked in most of the stories, with most of the contract killings being related to a clan’s honour or an individual’s loss of face.

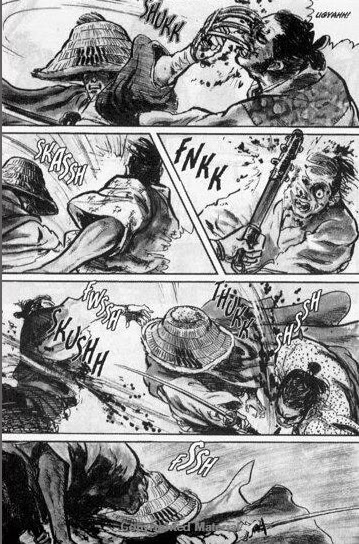

Not to say that the early volumes of Lone Wolf and Cub are lacking in the ingredients that typified the genre it was published under – action and sex. One of the early adventures involves Ogami Itto on a sea voyage, boarding the same ship as three fearsome brothers – the Bentenrai, each of whom are well-versed in a weapon of choice. Which means a proliferation of scenes like these:

As it turns out, the three brothers are enroute to protect the same client as Ogami Itto has been contracted to kill, and it ends in a face-off between the ronin and the three mercenaries. The icing on the cake is the death-speech of the brother who has the ill-luck to die by a diagonal throat-cut at Itto’s hands – the resulting arterial spray causes a keening sound referred to as ‘The Flute of the Fallen Tiger’ ( the same name as the story ). A Death-speech ( my term, I forget what the precise Japanese term is ) is the practise of having an ill-fated person, slashed at the hands of his enemy muttering a near-poetic sentence just before he dies, a good example would be O-Ren Ishii’s “That really was a Hanzo sword” line at the end of Kill Bill Vol 1.

Throughout the journey, Ogami Itto and Daigoro encounter other ronin who walked the land at that time. Japanese history tells us that during the Edo period, the rigid feudal structure of society had led to a proliferance of samurai who lost their masters in court intrigues or the machinations of the centralized shogunate. Most samurai found themselves assimilated as paid retainers of their lords or forced to the streets bereft of land. “Half Mat, One Mat, A Fistful of Rice” ( Volume 2) figures one such ronin, who makes his living holding streetshows in which he dares people to hit his head, sticking up through a hole in a mat, with a weapon of their choice. If they can go ahead and hit him before he dodges, they are free to scavenge his dead body with all the money they can fight. On meeting Ogami Itto and his son, the ronin suggests that Itto take to a better life to ensure that his son has a better future, to which Itto refuses, leading to a showdown between the two. Again, what is interesting here is not the actual fight itself, but the phiosophical argument between the two samurai, one who has no faith in the current society urging the other to reform himself and become a part of the social order once again. Another story “Parting Frost” ( Volume 4) is about Daigoro, as he searches for his father through the countryside – Kojima excels in drawing the silent montage of pages where the child walks, mute and uncomplaining, through the pouring rain. When he takes shelter in a temple, a wandering ronin sees him. Intrigued by the child’s shishogan, the eyes that show no fear or emotion, perfectly balanced in life and death, the swordsman follows the child from a distance, watching him get trapped in a forest fire without trying to help him. His curiousity is rewarded – Daigoro lives through the fire by sheer force of will – but in this child, the swordsman sees someone he can never be, and he lunges to kill him. Like I said, the line of reasoning followed by most individuals in the series is at odds with what we ourselves might consider logical or fairly obvious.

As Frank Miller put it in his introduction, this is a cruel, mad world that the characters inhabit.

It is in volume 3 that the origin story, part of which is narrated in Vol 1, the ninth chapter ‘The Assassin’s Road’, is fully explained, and the reader is given more details about the insidious dealings of the Yagyu clan, which sets into motion the chain of events leading to the transformation of the shogun’s executioner into an errant assassin. Koike’s storytelling skills have never been in doubt, but it is worthy enough to mention here that he gives us the backstory to a backstory in this tale, titled “White Path Between to the Rivers”. Masterfully told, as always.

However, the best story in this arc remains ‘The Gateless Barrier’ – the last story in volume 2, which deserves a post in itself. To be continued.

Because this is the first volume, and we have time on our hands, let’s do this very simply. Grab a chair and some popcorn, and let’s go through the stories one by one. It’s going to be tough for me, but I guess we can do it for one volume, right?

We begin the first arc with a cover by Frank Miller, an image of a blood-smeared samurai who’s obviously been in a fight, as the pile of bodies behind him demonstrates. He is hauling a cart in front of him, a cart with a cute baby in it. Remember this image, burn it in your mind, because it’s one of the most recurring themes in the series –the innocent child bearing mute witness to his father’s bloodshed. Nine stories, and the opening stubs of a series of articles at the back – one called The Ronin Report and the other Culture and Pop Culture. The articles are nothing an average Wikipedia-user wouldn’t know about, so we shall ignore them completely.