If there is one constant thread in my life, it is this realization that one thing leads to another, in the best possible way. Consider, for example, that after reading and gushing over the third book of The Daevabad Trilogy, I began to look around for the next hit (To be clear, I use the word in the context of narcotics, not in that of popularity) that might continue to further explore the medieval Islamic world. While it was tempting to swim around in the fantastical waters of djinn fiction, with the names I had mentioned in my review, I also wanted a book that was a little different and unpredictable.

I was also listening to podcasts featuring Shannon Chakraborty, to hear her thoughts about the series and to continue holding on to Daevabad and its pleasures. Among the interesting tidbits she talked about was her obsession with food, in particular historical recipes and writings on food. She spoke of a deleted scene in the second novel, which was to feature a cooking competition during Navasatem. And then, she went on to recommend a specific book called The Pasha of Cuisine.

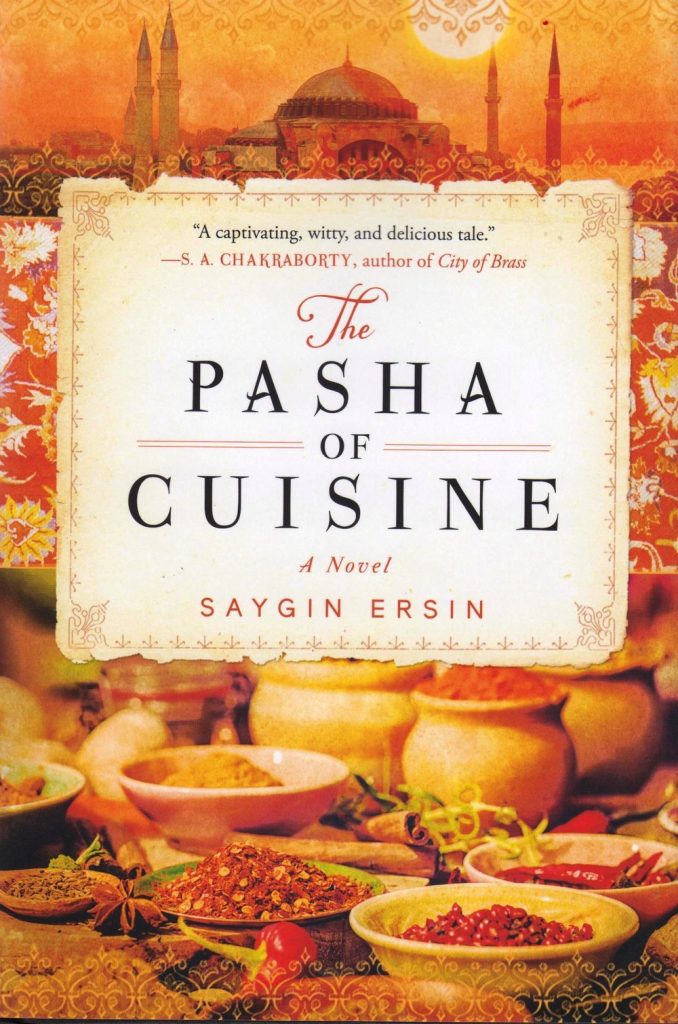

A hasty online search showed that the novel Pir E Lezzet, written in Turkish by Saygin Ersin, and translated into English by Mark Wyers, was available on the Hoopla app. It took about a week for me to get to the book, two days to finish it, and here I am, on a Saturday afternoon, babbling words of appreciation with stars in my eyes and a tremendous longing for kebabs and baklava.

The book, set in Ottoman Turkey, begins with a botched dinner party organized for the King’s Sword Bearer, a man of tremendous influence and a foul temper. The main course includes a leek dish, a vegetable that the guest is known to detest. As it turns out, he dreamily eats his dish, and then on realizing what it is, walks out in a huff, leaving the owner of the house to sputter at the cook for his disrespectful choice. The next morning, however, there comes an invite from the Sword Bearer — hand over the cook to be my personal chef, he says, and all is forgiven. The cook, already punished for his transgression, knew this was exactly how things would transpire and is ready to go.

We follow the young unnamed cook into the palace kitchen and its chaos, and the story slowly peels away secrets and histories that reveal the trajectory of the young cook’s life. In the space of the first few chapters, we realize that his presence in the palace kitchen, even his very existence, is no accident. There is the matter of his growing unease as he accompanies the guards to the palace, with a near-panic attack as he draws closer. The master of the kitchen, Head Chef Isfendiyar, seems to share a mysterious bond with him. And there is the matter of his interest in the Sultan’s Odalisque Harem, forbidden to all men other than the royal family.

Over the course of the next few days, the cook works not only to secure his culinary grip over his new master’s palate with his masterful use of flavors and ingredients, but also woos the latter’s harried assistants by cooking sweets and delicacies for them. At the same time, he takes on the responsibility of cooking for the Harem, making friends with Neyyir Agha, the Chief Eunuch working for the Haseki Sultan, who was “known to be one of the cleverest women that palace had ever seen, (and) wielded power over the sultan and the Harem at a very young age.” There are flashbacks that reveal the broader story of the cook’s journey, from his hidden background and innate culinary ability, to his apprenticeship at a bordello, and his journey to redeem both his title and his destiny. His quest involves a woman, if you must know, but it also involves coming to terms with his own emotional vulnerability. It is quite a journey.

Where Ersin excels is in making the story tread a fine line between historical fiction and fantasy. The chef whispers secret words as he cooks his magnificent meals and adds his ingredients one by one. Is his culinary skill related to magic or is it a real-world skill? They call him the Pasha of Cuisine, which is a title bestowed once in a generation, one that combines both the inborn ability to discern flavor and taste from an early age coupled with years of training. His dishes are shown to be able to influence both the emotions and the will of his diners. This paragraph, for example, gives a great insight into the way the Pasha’s abilities to heighten that relationship becomes important plot-points through the narrative.

Everyone knew that linden naturally brought on a feeling of calmness, and when fermented, that effect was heightened. Some religious scholars stated that fermented linden was an intoxicating substance that Muslims were prohibited from consuming. But if they were to have tasted a pastry made with the linden fermented by the Pasha of Cuisine, they wouldn’t have just advised against its consumption but banned it outright. In the hands of the Pasha, the innocent fermentation created a substance that tore down the barriers of logic that held back strong emotions and did away with all self-control. Whoever ate the fritters would forget about fear and loyalty, discarding tradition and rules in the process. The void created by the fermented linden would be filled with the sugar, the taste of which would be heightened by the sesame oil. The cook knew that sweet, one of the four basic tastes, was coupled with the element of fire, which was famed for its violence.

The flashback sequences are truly fantastic. The cook apprentices with Master Adem, a former Pasha, and then embarks on a voyage that goes beyond mere culinary school. He studies horoscopes under the eccentric el-Haki brothers, who teach him the medicinal properties of foods, and how food affects individuals based on their star signs. From the Lady of Essences, he understands not only the intricacies of spices, but also the means to soothe his wounded soul. And I must mention that from the moment the Lady of Essences makes her appearance and asks the cook why he came to her, the only face and voice I could hear was that of Tabu in her Vishal Bharadwaj characters. (One would assume the first mental image associated with such a character would be Aishwarya Rai in Mistress of Spices, but I have spent years trying to forget that experience.) All his journeys lead him, finally and fittingly, to Alexandria, where he has to ask a question, and one question only, of the Master Librarian. That question reveals, both to him and to us, the greatest secret of what it means to be the Pasha of Cuisine.

Spices are not related to intelligence, but to emotions. It is meaningless to know what spices are, whether they come from trees or roots or bark, or to memorize their natures, as it won’t be of any use to you. You should be able to inhale the scent of garlic and write two verses of poetry, compose an epic about the basil and mastic combining in your mouth, and extol the virtues of myrrh and a pinch of rosemary. Only then can you tell me that you’ve learnt about spices. You should look into the eyes of the person you want to mesmerize with your food and see into their hearts and soul, and at the same time be able to go through all the scents you know in your mind and decide which ones will either dampen or whet the appetite of their soul. Only then can I say that you’ve become the true Pasha of Cuisine.

I am in no way capable of talking about the historical accuracy of the novel. In the writer’s own words, “the Ottoman era is our very attractive “Fantasy Realm”. It is our Neverland, it is our Narnia, Westeros and Middle Earth. It has a magical atmosphere; very real on one side and very ‘dreamy’ on the other. Also it is so flexible. You can write a realistic political novel in that atmosphere and you can also write a mystical novel like the Pasha of Cuisine in the same atmosphere.” Below is an excerpts from a Turkish blog that talks about the culinary atmosphere in the Ottoman era. For the record, the reign of the Ottomans lasted six centuries, and it is unclear which period of those 600 years the book is set in. Warning: plot points in the description at the link below, so please do not click if you do not want to be spoiled.

Diverse Ottoman cuisine was amalgamated and honed in the Imperial Palace’s kitchens by chefs brought from certain parts of the empire to create and experiment with different ingredients. They were brought over from various places for the express purpose of experimenting with exotic textures and ingredients and inventing new dishes, and they served for 10.000 people every day! Meat was used in most foods. Kebabs and stews with every kind of meat were cooked in the palace kitchens. Birds such as chicken and duck were mostly roasted on a spit and you’ll read one of the most difficult recipe of The Ottoman Palace kitchen: Enveloped kebab which is cooked with different types of meat (turkey-partridge-chicken-quail). These poultries are put in each other in a size order, enriched with spices and put in oven. Have you seen green pilaf before? The Turks’ fondness for pilaf was such that it attracted the attention of travellers. It is an easy recipe, but among the indispensable tastes of the Ottoman cuisine. Spinach is boiled and crushed in strainer, then filtered with the help of a muslin. You can use this green water to cook your pilaf! How about a milk kebab? Lamp is boiled in milk, and meat is lined on a spit and slowly cooked.

http://maviboncuk.blogspot.com/2018/05/book-pasha-of-cuisine-by-saygin-ersin.html

Other than the Pasha of Cuisine himself, there are supporting characters known for their devotion to food and their craft, like the Mad Fishmonger Bayram, “the greatest fisherman not just of Istanbul, but of the Marmara Sea, the Aegean Sea, and the Black Sea, and even all seas around the world according to some”. He was also a master of cooking seafood, and his makeshift shack where he served favored guests was a secret unto itself. Why exactly he was considered mad is a story that is part of the book and I will leave you to find out for yourself. But the descriptions of Bayram’s cooking, specifically his fish soup, is both insightful and poetic.

Fish soup was one of the two greatest soups in the world, and the pinnacle of fish dishes as it had to be made perfectly, just like anything else that was difficult. A fish soup could not be “so-so,” “alright,” or “passable.” If done right, it would be soup; if done wrong, it would be rubbish, and that was that. It was one of the strangest dishes in the world. The more ingredients one added, the better it became. It did not have an absolute taste. The base flavor was fish, provided its smell was just right, but the soup changed taste with every spoonful. The first spoonful might be fish accompanied by celery stalk and carrot, the second might be onion and a small piece of fresh oregano, while the third could be the pure taste of fish scorched lovingly with the sweet taste of black pepper. The carnival of tastes continued until you finished the bowl. You would never guess what you would get with the next spoonful, and each sip was a surprise.

I will say, however, that the reason why the book has me rapturously singing its praises, goes beyond poetic food descriptions and exotic characters and locations. It is that the story takes a stand about art and the myth of the solitary genius that works tirelessly to achieve their goal and climb to the pinnacle of their chosen field. In a way, The Pasha of Cuisine is the anti-Whiplash, a movie I love passionately, but cannot get over how it leaves me shattered at the end of every viewing. The cook’s mentors (all but one, without spoilers) genuinely want him to succeed, and do so without compromising his life at the cost of his art.

Your soul is incomplete. You’re completely alone, and as long as you can’t mend the void within your soul, you’ll remain alone. Becoming the Pasha of Cuisine will not make your soul whole again. On the contrary, you will only be deserving of that title once you heal your soul.

Throughout the book, we know the cook not by his name, but by the title bestowed on him. We hear his name, for the first time, on the last sentence of the book. It is a triumphant end to his journey, bringing both closure and a sense of prophetic fulfillment. The epilogue that follows is a fine dessert, but even without it, I felt sated and full, like I just finished a masterful meal by a genius chef. This was followed by an overpowering urge for kebabs, but that’s TMI, I guess.