The glut of movies based on comics, in recent times, has added substantially to my View Queue. Reminds me of times I would scour second-hand magazine shops for the odd Cinescape, Cinefantastique or SFX for tidbits about the possibility of this actor playing that superhero, if this comic ever came to screen; which storyline would make for the greatest adaptation ever; would this little-known indie title fare better if it made a silver screen debut. And now it looks like every other 2 or 3-issue-old title has either been optioned, or is in pre-production already with the writer having banged out a first draft in two months and the artist involved in production design. Fuck, I realized that nearly every comic I know is being made into a movie.

One of the biggest changes in Hollywood dealings in recent times is the greater emphasis placed on the creator’s vision ( in case of non-corporate comics) and on the reliance on the overall back-story with the old-school mainstream superheroes. Sharp contrast to the times when auteur vision would take over – yes, Ang Lee, I am looking at you – with occasional scraps thrown in for the geek crowd, and the final product would leave me on the verge of tearing out my hair in rage. Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller’s Sin City did unbelievably well, and suddenly Hollywood woke up to the joys of the templated comicbook movie – the precise translation of panel to screen.

So, coming back to the deluge of newer and newer film productions devoted to adapting comics, it is evidently still not clear what will succeed and what won’t. Why does an Iron Man and a Dark Knight work at the box office, while a Punisher War Zone and a Spirit die ignominious deaths? Bryan Singer’s X-Men and X-Men 2 made mutants epitomise comicbook coolness, so why did Superman Returns explode like a planet near a red sun? I have some thoughts on those – maybe they’re not all the points that contribute to the success of an adaptation, but I think these are the most obvious.

1. Getting the Pitch right – This is, I believe, the most frequent stumbling block for a movie studio swayed by a director and overpaid, image conscious stars into bankrolling a movie that resembles the original comic in name only. Ang Lee’s Hulk is the most perfect example – a character primarily known for smashing things could not – and did not – work well as a psychological study of father-son relationships. The first two Superman movies were successful because they got the square-jawed do-gooder image of the character perfectly, the later ones made Superman the straight man, and boy, were they bad or what! One of the most jarring films I’ve seen of late was The Spirit. Yes, the one that featured Will Eisner’s character as interpreted by Frank Miller – and the movie just could not make up its mind about whether it was a noir take-off, a goofy take-nothing-seriously caper, a sex-violence-gore-filled piece of exploitation cinema. It was possibly Miller’s inexperience at work, but here’s a textbook example of how to NOT make a film. Sure, you can interpret characters your own way – but you cannot have a violent, bone-crunching fight sequence followed by a goofy Loony Toonesque show-off between the two characters.

2. Obscurity works. I will admit that I hadn’t heard of Daniel Clowes before I saw Ghost World. In fact, I will even admit that I had kind of assumed Ghost World would be about a world full of ghosts where a lone warrior, accompanied by the two hot girls on the cover of the VCD will wage a lonely war against supernatural beings by day, and totally do the girls at night. The movie of course had nothing to do with the scenarios my wretched mind had cooked up. It was a neat story about growing up in the suburbs and teenage alienation, and the fact that it was based on a little-known graphic novel worked in favour of both the film and its source – people like me went and discovered the sweaty, underground genius of Dan Clowes and the indie crowd loved the movie. What I am trying to say here is – a lesser-known graphic novel might just beat every other rule that I’ve laid out – it could include stars, it could manufacture its own interpretation of the source material, take tremendous liberties with the storyline, and could still win accolades. There’s no pressure to live up to the demands of the true believers – hell, did anybody know about A History of Violence before David Cronenberg made a movie out of it? Or Road To Perdition? When there’s no fan following in the first place, it gives the film-makers the liberty to make a film that stands on its own. If you read the original graphic novels, you’ll be shocked at the way the movies diverge from the books – not only adding characters and situations that weren’t there in the comic in the first place, but in both cases, changing the structure of the storyline to match the point Mendes and Cronenberg tried to get across. And they still worked, earned awards and created new readers for the books – in both cases, forcing DC Comics to reprint the books in newer editions ( they were originally published through Paradox Press, an original line under Warner that published mostly standalone crime comics).

3. Contemporary Relevance Comics have always reflected contemporary trends – Miller’s Dark Knight Returns is largely a reaction to the Reagan administration, a lot of anti-Thatcher sentiment appears in the 80s works of British writers like Pete Milligan and Alan Moore. But while backstories make sense to the followers and action sequences bring in the early weekend box office returns, the smart filmmaker knows how to add a layer of subtext that strikes a chord with the casual movie-goer and elevates his film beyond a generic popcorn fest. V For Vendetta was a comic set in a Thatcherian England gone fascist, while the Wachowski brothers, in their adaptation, made it more reflective of the prevailing political climate in 2006. Zack Snyder’s version of 300 also had a set of themes tacked on to its generally-straightforward storyline. The plus point of adding contemporary relevance to a comic book movie is that it gives the critics a hook to watch and review the film at a different level, and it leaves the current-affairs-savvy viewer happy that he “gets” what the movie is really about.

4. Stars don’t matter, actors do – There is this famous anecdote about Sir Alec Guinness, who could not stand the fan adulation about his character Obi-Wan Kenobi – and refused to attend Star Wars conventions. Probably Sir Guinness could not stand how Kenobi overshadowed every other role in his illustrious career, but this is a telling example of how a role brands an actor for life. All the more relevant with comic characters – fans have a tremendous emotional investment in characters they’ve grown up with, and if actor Joe Shmoe plays WhamPowBiff-man, he will always be identified as such. Christopher Reeve was a wonderful actor – look at his deadpan role of a theatre actor in Noises Off, but hey, he’s always remembered as Superman. Ditto Hugh Jackman. Non-stars have the ability to invest more fully into the character, rather than their own personal tics taking over the story. Jack Nicholson did a smashing job as the Joker in Tim Burton’s Batman, but at the end of the day, the character you saw onscreen was Nicholson playing a deranged lunatic, not the Joker. Tobey Maguire as Spider-man works in the first movie, but by the time he takes off his mask for every other scene in Spider-Man 3, it’s almost farcical – seeing Maguire the star try to assert his presence in the frame. In sharp contrast, look at Hugo Weaving as V or Robert Downey Jr as Iron Man, and you will be hard-pressed to believe these characters were overshadowed by the star-power of the actors involved.

5. Slavishness does not equal “Faithful to the source” Yeah sure, so the movie resembles the comicbook, the plot is directly from a memorable story arc and even the actors stand around just like the original panels. So why am I watching the movie in the first place? For that matter, why call it a movie at all – just call it a role-playing comic or something. It was Sin City that began this fad of panel to screen recreation, and while it was a bold visual experiment that worked really well – actors in stilted poses pretending they look anything other than dumb when emoting to the specifications of a printed page? Newsflash – they look very dumb. Voice-overs that echo narrative captions, excessive green-screen sets – I predict that in 10 years, all this will look as dated and groan-worthy as music videos from the 80s. And then we’ll all snicker about how we called Zack Snyder a “visionary” director.

6. Ignore the fans Yeah, you heard that right. Sure, fans weep and wail about every single detail, but here it is – they will always find flaws with the finished product, regardless of how good it is. So why bother at all? Keep the fan-service to a minimum, stick to a solid concept, make the changes that will translate the film properly onscreen – never mind the complaints about not being faithful to the source. The source comic exists as the template, but it’s moronic to think it’ll look or feel the same when real people are mouthing those lines or wearing those exact same costumes. Sam Raimi took liberties with quite a few aspects of the Spider-man mythos while making his movies – did anyone hear the howls of frenzy when the term “organic web-shooter” was bandied around? – but it paid off. The whole Harvey Dent/Two Face origin was reworked in The Dark Knight, but the brilliance of the overall package bulldozed over all fan-grumbles.

7. Stick to the same team for the sequels This one’s pretty much common sense coupled with a rudimentary knowledge of film production. A movie works not because of a concept, a script or a strong character, but because of a solid combination of the above with the vision of the principal crew, along with the equations that are shared between them and the cast. Your movie is a success, and then you decide to make the sequel, but with a different director – you’re effectively starting from scratch. Too many examples to mention here – consider the Batman sequels after Burton, X-Men 3, or even Punisher War Zone. The caveat: if your franchise tanked, feel free to reboot the franchise with a completely new team. Worked for Hulk and Batman, didn’t it?

8. Throw Joseph Campbell out of the window The classic “journey of the hero” bit that Campbell expounded has, quite frankly, been done to death by monkey-hordes of screenplay writers hacking out three-act scripts. It’s time to move on, already. Scripts that work beyond the usual good-against-evil spiel that’s been around, scripts that go beyond telling a basic vendetta tale that could be a generic action movie. One of the most telling examples of this is Mark Steven Johnson’s Daredevil, even though the movie was true to the spirit of the original comics, the pedestrian script let it down. Add to it the insipid writing in Constantine, the Punisher movies, the Fantastic Four movies, and others too numerous to mention – the ones in which you can predict in detail where the movie is going because you’ve seen hundreds like them before. All with the same cliched punchlines, the clipped dialogues, the juvenile foreshadowing and the soaring strings.

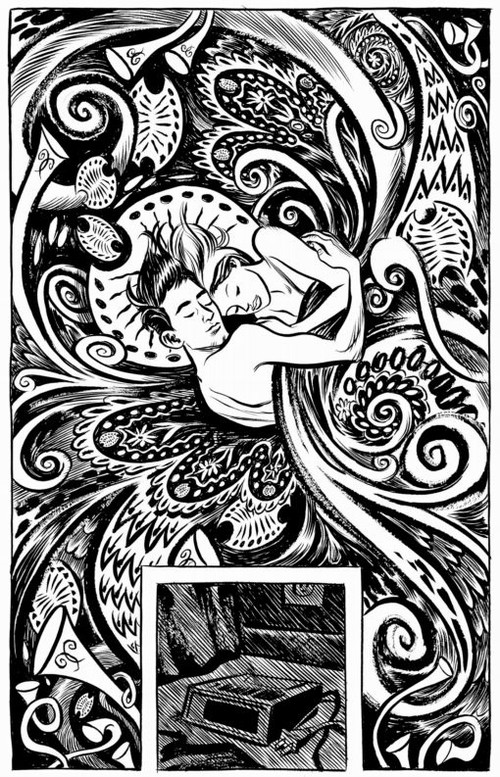

9. Avoid Alan Moore You would think film-makers would learn by now, but apparently not. So here’s the thing – Alan Moore writes comics. Comics, see? Not storyboards that can leapfrog onto the screen and make you pots of money. He writes his scripts with an eye on the artistic team he’s working on at the moment, and he writes stories that could probably be told on the screen, but not the way he wrote it. You can make a movie on Jack the Ripper, and it could be a thrilling look at a serial killer in Victorian England, but you cannot adapt From Hell. Call it something else, distance yourself from Moore the writer, and you’ll have a film that might work on its own, and you’ll have your dignity intact at the end of it all. Why expose yourself to an impossibly high standard that you know you are never going to attain anyway, when you can safely – y’know – write your own story and bring it to life? So the next time you want to adapt an Alan Moore comic, do yourself a favour. Watch From Hell, Constantine, LXG, V For Vendetta and Watchmen – and weep with disbelief at your own temerity. Quit it, there are better things to do that trying to adapt a Moore comic.