What is Lone Wolf and Cub all about? Simply put, it is a revenge story set in the Edo period, when the Tokugawa shogunate ruled over Japan. It’s the story of a wronged samurai named Ogami Itto and his baby son Daigoro, and how father and son seek to avenge their family honour in the face of relentless , powerful opponents. Above all, it’s a study of samurai life, Japanese society and human morals set in a time that is drastically different from our own, in an arena where the rules are substantially different. It’s historical fiction and it’s a pulp adventure and it’s a morality play. And yes, it’s one of the most influential manga series ever written, inspiring characters from different genres and cultures.

Lone Wolf and Cub, like most good things we know and love, was a product of the seventies. It was written by Kazuo Koike, a man much influenced by the gekiga movement in manga espoused by Yoshihiro Tatsumi, a move to more realism and experimentation in storytelling style. Koike opted for historical fiction served with liberal doses of sex and violence- much like Sanpei Shirato’s Kamui (1965-67). He began Lone Wolf and Cub in 1970 with a series of short stories illustrated by Goseki Kojima, then an up-and-coming manga-artist, serialized in Manga Action magazine. As the series progressed, the storyline became more complex, with Koike incorporating Zen philosophical observations in his stories, introducing little-known aspects of Japanese society, and brought twisted moral motivations to his characters. Kojima’s exquisite black-and-white brushwork held it all together, featuring detailed images of the Japanese countryside and settlements, brutal renditions of fight scenes, and quiet, multiple-page-spanning moments of the baby Daigoro and his father. The final product was 28 volumes in all, culminating in an ending which can be called- using the greatest of all understatements I can use – epic.

It was not until 1988 that the first English translations of Lone Wolf were published, bringing the series into mass consciousness of the Occidental world. Even before that, the ( untranslated ) series gained a lot of prominence among comicbook artists and the Japan aficionados, one of them being Frank Miller – who claimed, in the introduction to the first issue of the translated version of how 250 pages of back-to-back reading left him “babbling like an idiot”. It was First Comics that brought this series to America in the 1980s, just when manga and anime was seeping into the counter-culture consciousness. These 48-page comics were printed on high-quality paper, each of the issues bearing covers by noted artists like Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz and Matt Wagner. Early issues also had introductions by Miller, who revelled in his fan-boy love of the series by writing extremely florid descriptions of the series.

There were problems, though. The principal being that First Comics chose not to print the stories in their published order. Because of the assumption that the US market needed their stories more accessible (read: dumbed down), they chose to publish stories in chronological order. Which meant that the early First issues had the origin of Ogami Itto’s vendetta, instead of the actual storylines. Not a bad thing, but you know the problem about reading order – it’s like forcing someone to read The Magician’s Nephew before The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe just because events in Magician’s happen before the latter. Later issues had random storylines clubbed together from early Lone Wolf and Cub tales. All this is not necessarily bad, sometime or the other, First Comics would have been able to cover all the LW&C stories. That point was rendered moot by the fact that after publishing 45 issues of Lone Wolf and Cub, the company went bankrupt in the late 80s. As a result, only about 2000 pages of this epic tale were published in English, roughly a fourth of the complete story. And it has to be said – the story hadn’t even got to the good parts.

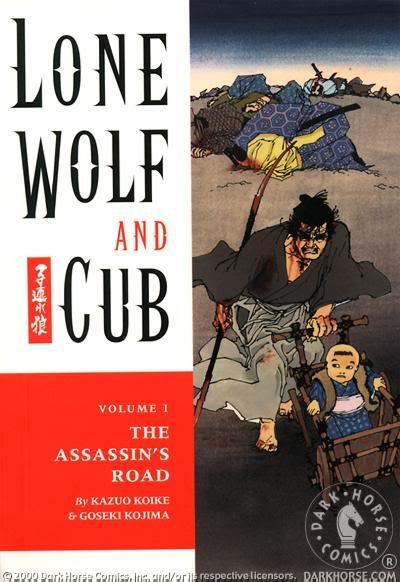

Enter Dark Horse comics, twelve years later. The manga boom had arrived in the USA by then, with companies like Viz and Tokyopop already bringing out popular titles that had found extended reader-bases, and Dark Horse following suit by reprinting some of the classic series – Masumone Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell and Appleseed, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Domu and Akira. Based on a deal with Koike Shoin publishing, Japan, ( incidentally, owned by Kazuo Koike himself, in sharp contrast to publisher-owned manga properties, the writer had obtained the rights to all his series from the original publisher Fuso-sha) Dark Horse acquired the rights to bringing back into print Lone Wolf and Cub. Instead of choosing to go the normal 32-page or 48-page pamphlet form, the company opted to print the series the way it was originally collected in Japan, 28 4-inch by 6-inch volumes of 250-300 pages each. Not only was this format in sync with the new publishing model followed by manga companies, it also served to keep costs down, so that the volumes cost 9.95$ each when they came out, a perfectly fair price to bring in a healthy reader-base for this long series. Dana Lewis along with Studio Proteus, one of the pioneers in manga translations, undertook new translations for the series. The other concession made for the American market was that the manga was flipped – which means, the reading order of the original artwork, back-to-front, right-to-left was changed to the western left-to-right format. This was done by reversing the artwork, resulting in incongruities like almost characters in the series becoming left-handed. Covers were by American artists, with all of Miller’s covers for the First comics being reused initially and newer covers designed by Mike Ploog, Matt Wagner, Vince Locke and Guy Davis.

The twenty-eighth volume of the Dark Horse reprint came out in December 2002. Dark Horse stuck to a release schedule of a volume per month, quite a foolhardy venture, considering that the editorial process had to be put into place for 300 or more pages per month!

I have read and reread the volumes a number of times since I got them, both in digital and actual formats. There have been more works by Koike/Kojima published by Dark Horse after that, the ten-volume Samurai Executioner and the currently ongoing Path of the Assassin. But it’s Lone Wolf and Cub that keeps calling me back every now and then. And the more I look around, it looks as if there isn’t anyone comprehensively writing about how good this series gets as it progresses. I know a lot of folks who start reading it, and lose interest by the 10th volume, just because the story gets a little repetitive. Trust me, Koike and Kojima have crafted a story that demands your attention. It requires the reader to focus on a journey without worrying about how long it will take or where it will go. Because unlike stories about super-humans or larger-than-life franchises which have to go on, so that the creators and the publishers can milk all possible storytelling avenues dry, Lone Wolf and Cub has an ending. It becomes all too apparent to the reader by the time the storyline enters its second arc (I have mentally divided the series into a number of arcs, each arc representing a logical progression of Ogami Itto and Daigoro’s journey ) that the Koike and Kojima have no intention of running in circles.

So this is what I am about to do. Over the period of the next couple of days ( or weeks. You know my writing habits) I am going to write about each volume of Lone Wolf and Cub. There will not be spoilers, for the some of you who have not read the series yet and want to read it someday. Some will have read the series already. Most, I gather, don’t give a flying fart about what I write or am going to write, so this is your chance – give this idea-space a miss unless you want to know more about this amazing series. Right now would be…uh…a good time to really figure out if you really need me on your f-lists.

Onward, then.